Executive Summary

The international education sector has witnessed a recent explosion of literacy and numeracy programs in Southern contexts. Many, if not most, of these programs have included teachers’ guides that provide scripted or semi-scripted lesson plans to teachers. Although the provision of teachers’ guides has been a consistent element of the programs, there has been far less consistency in how these teachers’ guides are viewed within the sector. Some argue that scripted teachers’ guides provide important scaffolding for teachers implementing new instructional methodologies (Grossman & Thompson, 2008; Stockard et al., 2018). Others believe that scripted guides are a particularly important resource for teachers in countries at low levels of development (Barber et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2000). Recent research has shown that in Kenya, teachers’ guides are effective and highly cost-efficient components of literacy and numeracy improvement programs (Piper, Zuilkowski, et al., 2018). However, some criticize the existence and utilization of these structured approaches because of their potential to stifle teacher creativity and reduce teacher autonomy (Dresser, 2012; Valencia et al., 2006).

Evidence for either point of view is limited in the Global South. Those who have defended teachers’ guides often discuss them as a monolithic whole instead of advocating for potential elements of their design. In contrast, those who are against the guides reject them out of hand rather than noting which characteristics of teachers’ guides are either beneficial or harmful to lesson quality.

In this context, RTI International undertook a detailed analysis of the design and utilization of teachers’ guides in 19 projects in 13 countries. The research study had four components. The first was a detailed analysis of the characteristics of the physical teachers’ guides, including their length, layout, and level of scripting. The second was a quantitative analysis of the scripting levels of these teachers’ guides to investigate whether the scripting level correlated with program impact (i.e., to determine whether more scripting led to greater impacts on learning outcomes). The third was observations of teachers in classrooms across four countries (Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, and Malawi) to determine how teachers responded to teachers’ guides with different components and examine how they used the documents in their classroom practice. Finally, the fourth research component was interviews of teachers, after observing them, to learn more about the instructional modifications they made to the teachers’ guides and identify any patterns in their adherence—or lack thereof—to the content in the guides.

We compiled the quantitative impact results of recent literacy programs and found that programs that used teachers’ guides achieved significant impacts on learning outcomes. On average, we found that the causal gain in oral reading fluency resulting from programs with teachers’ guides was 6.1 correct words per minute (Piper, Sitabkhan, et al., 2018). This gain represents a substantial and meaningful impact on learning. Note that, in addition to teachers’ guides, we show that many other factors can determine the size of this causal impact, including teacher professional development and coaching designs and implementation strategies; these factors are not accounted for in this analysis.

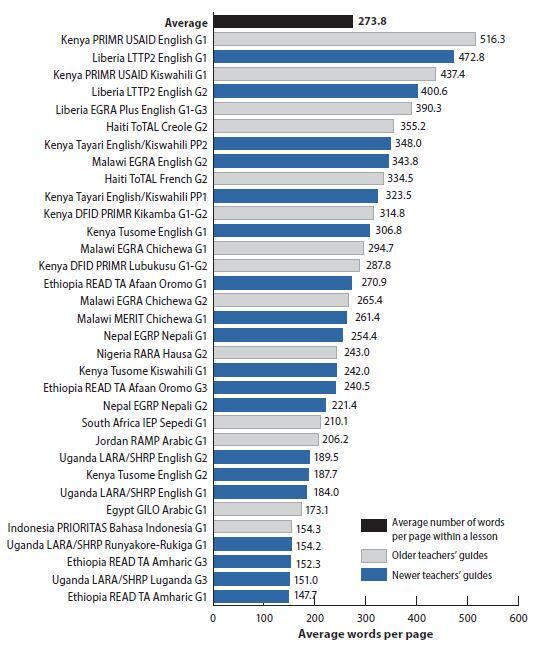

One of the key comparisons in our analysis focused on the number of words in each lesson. We found that the average lesson had 836 words and that some programs had very long lessons (3,679 words for Haiti Tout Timoun Ap Li [ToTAL] in French for grade 2), whereas others had very short ones (e.g., 154 words for Indonesia Prioritizing Reform Innovation, and Opportunities for Reaching Indonesia’s Teachers, Administrators, and Students [PRIORITAS] in grade 1 and 235 words for Nepal Early Grade Reading Program [EGRP] in Nepali for grade 2). Our analyses showed meaningful differences in the length of lessons between older and new programs. Over time, it appears that programs were generally reducing the length of the lessons to increase utilization and ease of use. This trend was observed even within countries over time. For example, the Kenya United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Primary Math and Reading Initiative (PRIMR) English program for grade 1, which was implemented from 2012 to 2014, had many more words per lesson (1,549) than the later, national-level Kenya Tusome Early Grade Reading Activity (“Tusome,” or “Let Us Read”) English program (2015–2019), which averaged only 282 words per page.

Our research revealed that the designs of the teachers’ guides developed and used within RTI’s literacy and numeracy improvement programs varied widely. Design elements with wide variations included the number of words per page, the number of pages in a lesson, the number of activities in a lesson, whether the teachers’ guide used icons, and whether the guide contained thumbnail images of the student book pages to simplify the work of the teacher. Our findings demonstrated that the attractiveness of the guides increased over time and that their bulkiness decreased.

We used the variation in the designs of the teachers’ guides to develop a scripting index to compare all the teachers’ guides in terms of the level of detail they provided to teachers. We found a moderate, negative relationship between the level of scripting and improved learning outcomes. For every additional 10 percentage points on the scripting index, program impact decreased by 1.4 correct words per minute. These results were not always statistically significant depending on the model and control variables. In other words, although our analysis revealed that programs with scripted teachers’ guides improved learning outcomes, having too much scripting could detract from overall program effectiveness. Instead, we found that teacher’s guides that provided fully scripted lessons at the beginning of the teachers’ guide and shifted to structured lesson plans instead of scripted lessons tended to improve learning outcomes. We use the term structured to refer to lesson plans that provided detailed information on the content of the lesson and a clear and consistent instructional model. By this definition, teachers’ guides that taper off in their level of scripting would be considered structured, and not fully scripted.

We observed teachers using the teachers’ guides in classrooms. The observational protocol examined both the number of changes per 30-minute instructional block and the percentage of modifications made during that period that detracted from the lesson. Some modifications improved the quality of the lesson (26 percent of all modifications), but most changes detracted from the quality of the lessons (59 percent). Our analyses examined the relationship between the number of modifications and the percentage of negative modifications and compared fidelity (i.e., number of modifications) and quality (i.e., the percentage of negative modifications). In general, as the number of modifications increases, the percentage of negative modifications also increases. This relationship suggests that, in some contexts, increased fidelity to the teachers’ guide would improve the quality of instruction. The sampled Kenyan, Malawian, and Ethiopian teachers had largely similar results with respect to the number of modifications per 30 minutes, but the Kenyan teachers made many fewer negative modifications. The Ugandan and Ethiopian teachers had similar percentages of negative modifications, but Ugandan teachers made more modifications per 30 minutes. The results suggest low-quality lessons with low fidelity in Uganda, medium-quality lessons with medium fidelity in Malawi and Ethiopia, and high-quality lessons with high fidelity in Kenya.

The types of changes that teachers made varied widely, as our findings show. Content additions occurred when teachers added content to the lesson, and content omissions were when they left something out. Structural changes occurred when teachers changed the format or method of the lesson observed. Teachers were coded as skipping full activities when they simply did not do a portion of the lesson, and a partial activity skip was when the teacher skipped over part of the lesson.

The changes that teachers made seemed to be influenced by the design of the teachers’ guides. In Uganda, teachers skipped significant portions of activities (37.8 percent), often because the Ugandan teachers’ guides required that the teacher skip back and forth within the guide to find the instructions and the content of the lesson. In Ethiopia, 14.5 percent of the activities were skipped entirely, likely because the teacher had to skip back and forth in the guide to find what they were to teach at particular points in the lesson, and because lessons did not start on new pages in the guide. Malawi’s teachers added a substantial amount of content (46.7 percent), seemingly because they were encouraged to deviate from the teachers’ guide by the program. The Kenyan teachers were most likely to make structural changes (63.9 percent) to the lesson described in the guide, primarily because they were relatively comfortable with the teachers’ guides and how they were used, and therefore could make changes to improve the quality of their teaching.

Counterintuitively, emphasizing fidelity to a relatively simple teachers’ guide increased the likelihood that a teacher could be responsive to his or her students.

Interviews with teachers revealed interesting decision-making for deviations from the teachers’ guide. Unfortunately, the most common reasons given to explain changes from the teachers’ guide were either unintentional missteps or difficulty teachers encountered when using the physical guide. The reasons varied across projects, but how frequently the teachers reduced group work and interactive aspects of the lesson and opted for more teacher-centered activities was striking. The teachers noted that the design of the teachers’ guides affected their choices, explaining that the difficulty of navigating the text or physical layout of the guides reduced their likelihood of using the activities outlined for each lesson.

As a result of the research presented in this report, RTI developed a set of guidelines that future RTI programs should use when developing teachers’ guides. Table ES-1 presents essential guidance that should be implemented in materials for new RTI programs as well as revisions of existing RTI materials.

The items listed in Table ES-2 represent suggested guidance that planners should consider during the development or revision of teachers’ guides.

Introduction and Literature Review

International education assistance has seen recent expansions in programs that aim to improve literacy outcomes. These quality improvement initiatives often use teacher’s guides with scripted lesson plans that support teachers to implement a new pedagogical method. These lesson plans directly refer to content in student books. Some researchers prefer the term lesson plans rather than teachers’ guides to describe these docuemnts, if teachers’ guides are considered to be general guidance for the teacher rather than specific lesson guidance on a daily basis. This differs by context and country. For the purposes of this report, we refer to sets of lesson plans as teachers’ guides. We differentiate between fully scripted teachers’ guides, which write out the entirety of what teachers should teach on a daily basis, and structured teachers’ guides, which may include some scripted lessons, but are not necessarily fully scripted for the entirety of the guides.

Teachers’ guides have been developed as part of several RTI-implemented literacy programs over the past decade. We analyzed guides from 19 of these programs in 13 counties and present the results in this report. These programs have been similar in terms of their specific emphasis on early grades or early years, a focus on literacy and sometimes numeracy, components that provide ongoing professional development to teachers, coaching, and the utilization of student assessment to measure impact.

RTI-developed teacher’s guides have ranged from heavily scripted to more lightly scripted; some programs have student books but have not used teachers’ guides at all. As we will show, many of the programs that have used scripted teachers’ guides have been quite successful in improving reading outcomes, in disparate countries and languages (Brunette et al., 2018; Gove et al., 2017; Piper, Zuilkowski, et al., 2018). The combination of initial successes and client-driven demand to use scripted guides has pushed RTI and other implementers sometimes to defend the use of scripted lesson plans despite having neither in-depth research that explains the range of options available nor guidance on which of these options have evidence of success.

Very little is known, across the Global South, about the level of scripting that exists in instructional materials used. Even less is known about how the level of scripting affects teacher usage of the materials and instructional decision-making in the classroom, how the level of scripting affects teaching quality, and ultimately learning outcomes. This information is scarce because very little research incorporates a systematic review of particular types of scripted lesson plans, nor does a structured process exist that helps guide new literacy or numeracy programs in determining what kinds of teachers’ guides are ideal for supporting teachers.

Evidence supporting teachers’ guides with scripted lesson plans (Grossman & Thompson, 2008) has been building (Piper, Sitabkhan, et al., 2018). The notion of scripted lesson plans in teachers’ guides comes from the idea that direct and explicit teaching scaffolds teachers’ ability to effectively teach literacy skills, particularly the key components of reading (e.g., phonemic and phonological awareness, fluency, comprehension) (Rosenshine, 1995; Rupley et al., 2009). A recent metanalysis of direct instruction methods, which often use structured or scripted teachers’ guides, showed substantial effects on learning outcomes (Stockard et al., 2018). The magnitude of this analysis, drawn from 328 studies and 393 reports, is substantial, with average treatment effects of 0.54 standard deviations (SD) overall, and 0.51 SD for reading programs. Hattie’s (2008) analyses showed that structured programs have meaningful impacts on learning outcomes, as well.

Although the research base in the Global South remains modest, there are some studies that address how scripted teachers’ guides could affect instruction at a systems level. An influential McKinsey & Company report has suggested that poorly functioning systems should use a scaffolded approach with scripted teachers’ guides (Barber et al., 2010). Piper, Zuilkowski, et al. (2018) showed that including teachers’ guides was a cost-effective investment in improving literacy and numeracy outcomes in in a Global Southern context such as Kenya, yet their research design did not answer which type of teachers’ guide was most effective. However, there is resistance from those who believe that scripted lesson plans limit the creativity and agency of teachers (Dresser, 2012; Valencia et al., 2006). The concerns about scripted teachers’ guides are not only stylistic, as Sailors et al. (2014) showed that while teachers viewed that the teachers’ guides helped them feel more comfortable teaching reading, there was little impact on classroom pedagogical methods. The literature cited in this section shows a small but growing evidence base for the impact of structured teachers’ guides on learning the Global South but there remains a significant gap in the literature related to how various levels of scripted teachers’ guides affect learning outcomes and how teachers respond to these differences in teachers’ guide designs.

Research Objectives and Design

To better understand how the structure of lesson plans may affect teachers’ ability to improve learning outcomes and how RTI’s scripted teachers’ guides compare with each other on the ability to improve outcomes, a research team carried out a systematic study in 2017 of teachers’ guides from RTI-led programs. The teachers’ guides scripting study asked the following research questions (RQs):

-

RQ1. How does the level of scripting differ across projects?

-

RQ2. Does the level of scripting have a relationship with how teachers use the teachers’ guide?

-

RQ3. Does the level of scripting impact the amount of time it takes for teachers to learn to do the routines correctly?

To answer the research questions, the study team collected both quantitative and qualitative data from five sources.

First, we developed a quantitative analysis database to answer the first research question. The research team investigated 34 teachers’ guides in 19 projects across 13 countries and created a database that evaluated the 34 teachers’ guides across a large number of quantitative measures.

Second, the research team selected four lessons in each teachers’ guide. Depending on the number of pages in the guide, the lessons that were found 20, 40, 60, and 80 percent of the way through the guide were selected. For each of the selected lessons, we worked with project staff to translate into English as needed, and to analyze the content of each guide more deeply, focusing on activities, length, and page format, among other characteristics.

Third, a selection of RTI’s international education projects was selected for qualitative data collection based on the level of scripting of their teachers’ guides. The purpose of the qualitative analysis was to examine how teachers used the lessons in the guides in classrooms. Literacy improvement projects in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Kenya, in addition to two projects in Uganda, were chosen since they represented a range of teachers’ guide designs with respect to scripting level and complexity. We spent a week with the project team in each country and applied a structured protocol to observe classroom teachers using the guides. These classrooms and schools were selected by the projects because they were effectively implementing the program (above the 75th percentile, as defined by the project), were in a rural setting, and were less than 2 hours from the capital city.

Fourth, after each classroom observation, we interviewed the teacher. The focus of the interview was to understand how they viewed the usability of the teachers’ guide, how their use of the guide changed over time, and what their reasoning was for making the changes from the teachers’ guide that they did.

Fifth, we reviewed project impact evaluation documents to determine the causal impact of the program or, if the program did not have experimental research available, the year-on-year gains in learning outcomes in national programs. Program impact, measured by gains in oral reading fluency, was compared with each program’s scripting level to investigate whether there was a relationship between scripting and program impact.

Instruments and Data Collection Methods

Quantitative Desk Review of Teachers’ Guides

The systematic desk review was designed to collect qualitative data on past and current RTI-implemented programs. The research team analyzed key components of the design of the teachers’ guides, including the number of pages in each guide, the number of pages per lesson, the number of words per lesson and page, and the types of activities that the lesson plan included.

In addition to this general analysis, we undertook a detailed analysis of four lessons from each teachers’ guide. The teachers’ guides were broken into quarters based on the total number of lessons. As noted previously, one lesson from each quarter of the guide was reviewed, at 20, 40, 60, and 80 percent of the way through the guides. Using multiple lessons from throughout the guide (rather than looking at four consecutive lessons at a particular portion of the guide) allowed the data to be more representative of the range of lessons within the guide. Additionally, this method of review allowed for analysis of variation within a single guide—revealing whether the amount of scripting was reduced in lessons later in the year. A member of the study team worked with local education officers to translate each of the four lessons into English as needed.

The review included 34 teachers’ guides from 19 RTI-implemented programs in 13 countries. For several programs, multiple grades or languages were reviewed, so that a wide range of languages and teachers’ guide types could be analyzed. The specific teachers’ guides analyzed are shown in Table 1. We consulted with materials developers and language experts from each project to undertake the analysis of the materials in each country.

Quantitative Comparisons of Teachers’ Guides

Teachers’ Guide Technical Differences

In this section of the report, we present the findings of specific analyses of the design of the teachers’ guides. First, we examined each teachers’ guide to determine how many lessons were taught in each plan. The average number of lessons in the teachers’ guide was 144, with a range of between 135 and 192 lessons. There were no clear patterns in the number of lessons by grade, with preprimary teachers’ guides averaging 135 lessons, and grade 2 having 150 lessons.

Our next analysis examined the number of pages within an average lesson. The length ranged from 1 to 11 pages, with an average of 3 pages per lesson. The preprimary lessons (from the Kenya Tayari program) averaged 1 page per day, which is shorter than the average. Comparing the older with the newer teachers’ guides, it appeared that RTI’s teachers’ guides have shortened over time, with the 2016 Uganda Literacy Achievement and Retention Activity/ School Health and Reading Program (LARA/SHRP) lessons in the languages of Luganda (grade 3) and Runyakore-Rukiga (grade 1), and the 2015 Nigeria Reading and Access Research Activity (RARA) lessons in Hausa (grade 2), as notable exceptions at 6 pages long. Note that countries with more than one round of materials development reduced the number of pages. For example, Malawi Early Grade Reading Improvement Activity (MERIT) lessons in Chichewa for grade 1 were shorter (1.3 pages) than Chichewa grade 1 lesson plans prepared under the predecessor program (Malawi Early Grade Reading Assessment [EGRA]; 5.3 pages). In Kenya, USAID PRIMR English lessons for grade 1 were 3.0 pages, and the later Tusome English grade 1 lessons were 1.0 pages long.

Figure 1 presents the average number of words in each lesson graphically. We differentiate between the “older” teachers’ guides, which are indicated with gray bars; and “newer” teachers’ guides, which are indicated with blue bars. Finally, the black bar shows a simple average of the number of lessons in each guide. Some older programs had shorter lessons, including Prioritizing Reform, Innovation, and Opportunities for Reaching Indonesia’s Teachers, Administrators, and Students (PRIORITAS; 154 words) as the shortest guide overall. The trend has been toward shorter lessons with respect to number of words in a lesson. One example of this trend was found in Kenya, where the USAID PRIMR English guide for grade 1 had 1,549 words per lesson, whereas the Kenya Tusome English guide for grade 1 had 307 words (i.e., one-fifth the length of the previous teachers’ guide). We calculated the average number of words in an RTI-designed lesson at 836, although this number was increased by some of the older teachers’ guides from grade 2 Haiti Tout Timoun Ap Li [All Children Reading] (ToTAL) French (3,679); grade 2 South Africa Integrated Education Program (IEP) Sepedi (1,944); grade 1 Liberia Teacher Training Program, phase 2 (LTTP2) English (1,891); and grade 2 Haiti ToTAL Creole (1,687). Interestingly, grade 2 the 235-word Nepali lesson plan for the Early Grade Reading Program, Nepal (EGRP) fell under the same “scripted lesson plan” umbrella as did Haiti ToTAL French (3,679 words), although the latter was 15 times as long.

The length of these lessons has implications for teaching as our study collaborators noted that their teachers struggled to simply read all of the words in the guide, let alone teach them.

Figure 2 compares the numbers of pages per lesson and the numbers of words per lesson to present the average number of words per page within a lesson. Agglutinating and nonagglutinating languages (e.g., Luganda vs. English) have different word lengths, making this interlingual comparison of word counts difficult. However, as indicated earlier, it is worth noting that while the developers of RTI’s teachers’ guides may have been focused on reducing the number of pages in a lesson, they do not appear to have focused on reducing the number of words on a page.

These data also reflect the different graphic design of teachers’ guides. Even in programs that were teaching lessons in English (and therefore would have had similar word lengths), we found variances, with 516 words in Kenya USAID PRIMR English pages (grade 1) and 473 words in Liberia LTTP2 English pages (grade 2), compared with only 151 words in Uganda LARA/SHRP English pages (grade 3). Paying more careful attention to the number of words on an individual page might help some programs to reduce the number of pages, if it is page length that makes a lesson seem particularly long for teachers.

Typical lessons include several activities, such as phonemic awareness mini-lessons or reading comprehension routines, as Figure 3 shows. The Malawi EGRA Chichewa guide for grade 1 had the most activities (15.5) in each lesson, and the mother-tongue programs for both Nepal EGRP (12.0 for Nepali in grade 2 and 11.5 for grade 1) and Uganda LARA/SHRP (10.8 for Ruyakore-Runiga in grade 1 and 10.2 for Luganda in grade 3) had more than 10 activities in a lesson. On the other end of the spectrum, Jordan Early Grade Reading and Mathematics Initiative (RAMP) focused on just one activity per day. The average number of activities per lesson across the programs was 6.8, with most of the teachers’ guides falling between 5 and 8 activities in the lesson. Based on the classroom observation data we present, some of the activities at the end of the lesson may be skipped. Therefore, care should be taken to avoid overloading individual lessons with too many activities.

Teachers’ Guides Activity Comparisons

This section of the report focuses on the distribution of activities within the lesson. We coded the activities from each lesson into the five components of reading (i.e., phonemic awareness, alphabetic principle, fluency, vocabulary, and composition), with writing serving as a sixth category. We identified wide differences between programs in the distribution of activities in a lesson.

To create Figure 4, we took the raw number of activities in the six areas of instructional emphasis and looked at the percentage of activities in the reviewed lessons by these six areas. These averages indicate that phonemic awareness comprised a much smaller percentage of instructional activities in grade 3 (3 percent) than in grade 1 (19 percent), as expected. In contrast, reading comprehension represented a higher percentage of time in grade 3 (30 percent) than in grade 1 (18 percent). Second-language programs spent more time on vocabulary (20 percent) than did the local-language programs from grade 1 to grade 3, as expected. Materials developers should consider whether the spread of activities is developmentally appropriate for the language and grade being taught.

Impact of Programs with Teachers’ Guides

This section of the report focuses on whether programs that include scripted lesson plans improve learning. The results presented combine review internal and external impact evaluations for our programs’ impacts on learning outcomes.[1] Few of the evaluations available on the RTI collaboration website (https://shared.rti.org) or on the Global Reading Network website (https://globalreadingnetwork.net) included effect sizes to allow for simple comparisons, so we focused on the gains in oral reading fluency and request that readers evaluate this analysis carefully given the differences in word length across languages.

Note that the results presented are the causal gains in oral reading fluency between baseline and endline as obtained from impact evaluations, or the year-on-year differences in oral reading fluency for the large-scale programs had multiple assessment time points. This analysis was weakened by the fact that average word length differs by language, that many of RTI’s projects did not yet have impact evaluations, and that where such evaluations existed, they did not necessarily cover the grades and languages selected for the teachers’ guide analysis.

With those caveats, the average impact of RTI’s programs that include structured teachers’ guides was 6.1 correct words per minute. The magnitude of this causal impact shows that the average RTI reading program increased learning outcomes by the equivalent of nearly half a year of additional schooling, on average. This is a significant impact on learning outcomes, though it is important to note that the length of the words in different languages vary significantly. It is important to note that RTI programs also included teacher professional development, instructional support, local government capacity building, and many other factors. However, given the history of relatively meager impacts of donor-funded education programs, it is notable that RTI’s education programs (including structured teachers’ guides) have achieved substantial impacts on oral reading fluency, with some exceptions.

Developing a Scripting-Level Model

This section of the report addresses our teachers’ guide data in a way that allows us to present what we believe is a cautious view of “scripting.” We define scaffolding as the guidance that the teachers’ guide offers to the teacher on what to teach, and scripting as the amount of words given to the teacher to explain what he or she should say. Given the wide variation in our program designs, we decided to develop a simple analysis of scripting. First, we ranked the teachers’ guides by the number of pages per lesson, and then we compared that with the number of words per page.

Some programs put a large quantity of information on a page. For example, Kenya USAID PRIMR English (grade 1) had more than 500 words on a page, but there were only 2.5 pages per lesson. Some programs, however, used many pages but had few words per page page. Uganda LARA/SHRP in Luganda (grade 3) had 6 pages per lesson, but only 150 words per page. If we had analyzed the number of lessons, we might have considered the grade 3 materials for LARA/SHRP in Luganda to have been more scripted than the grade 1 materials for Kenya USAID PRIMR in English, but if we had considered only the number of words on the page, we would have drawn the opposite conclusion.

A regression analysis investigating the relationship between words per page and pages per lesson showed no relationship, and only 0.3 percent of the variation in the words per page was explained by the pages per lesson. These findings suggest that scripting, with this broad definition, is structured very differently in different projects.

Using these data, we created a scripting index. First, we ranked the projects by the number of pages per lesson, assigned the project with the highest number of pages per lesson (Haiti ToTAL in French, grade 2) 50 points, and then assigned other projects the proportion of 50 points corresponding to the number of pages per lesson relative to that of Haiti ToTAL. Next, we ranked the projects by the number of words per page, gave the project with the highest number of words per page (Kenya USAID PRIMR English, grade 1) 50 points, and then gave the other projects the proportion of 50 points corresponding to the number of words per page, relative to Kenya USAID PRIMR English. Then, we added the points from the pages-per-lesson scripting and words-per-page scripting to generate the total scripting index score out of 100.

We present this scripting index in Figure 5. The most heavily scripted program was Haiti ToTAL in French (grade 2), which scored 82.4 out of 100. The least scripted program was Indonesia PRIORITAS in Bahasa Indonesia (grade 1), which had a score of 19.5. The average value was 40.2, and most of our most recent programs were less scripted than the overall RTI average, except for Liberia LTTP2 in English (grade 1). Among our recent or active programs, Ethiopia READ TA in Amharic (grade 1) and Kenya Tusome in English (grade 1) were the least scripted.

Relationship Between Scripting Level and Program Impact

In this section of the report, we cautiously move to a discussion of the relationship between scripting level and program impact. The large number of RTI programs with teachers’ guides and impact data allowed us to analyze the relationship between teachers’ guide scripting and program impact. With that caveat, we fit a regression model of the relationship between our scripting index and program impact. When we included all of RTI’s programs, we found that a regression model including the level of scripting explained 12 percent of the impact on learning, and that the relationship was negative. For every additional 10 scripting index points, program impact decreased by 1.4 correct words per minute. The findings were similar when we limited the analysis to the larger-scale, more recent programs. This crude quantitative analysis does not account for the variety of other factors that explain the impact of literacy programs, and in fact, the results show that a full 88 percent of the impact on learning is explained by factors beyond the level of scripting in the teachers’ guides. These may include the unique linguistic structures of languages, the effectiveness of the teacher professional development and coaching structures that were implemented alongside the teachers’ guides, the government ownership of the initiative, and of course, the actual quality of the teachers’ guide themselves. An alternative explanation of this finding is that the newer programs, that have less scripting, also benefit from having had learning on how to design and implement these literacy programs, and it may be that the improved design of the programs, and not the scripting level itself, could account for the larger impact of less scripted teachers’ guides.

Although we present these data cautiously, the relationship between scripting and learning outcomes should inspire us to reflect on the relationship between our heavily scripted programs and learning outcomes. Put another way, this analysis suggests that even within the context of the same country and similar projects (e.g., Kenya USAID PRIMR in English, which was more scripted than Kenya Tusome in English, both for grade 1), the impact can vary substantially, with the more scripted program being less effective, and more “structured” programs being more effective. The gains in Kenya Tusome were far larger than those experienced by Kenya PRIMR.

We are not claiming that the relationship is causal, but we are simply highlighting the negative relationship between scripting and program impact beyond a basic threshold of impact. Scripting appears to improve learning outcomes in general, but beyond a basic threshold of scripting, it can detract from overall program effectiveness.

Qualitative Comparisons

Classroom Observations in Four Countries

For the classroom observations, a structured protocol was used that built on the findings and research tools developed in a previous classroom observational study undertaken in Malawi (Mattos & Sitabkhan, 2016). The sample of teachers and the dates of observations are presented in Table 2.

Results on Lesson Fidelity and Quality

Fidelity

We wanted to know how closely the teachers were following the details in the teachers’ guide. To calculate fidelity, we looked at lesson length. The shortest lesson was 25 minutes, and the longest was 1 hour and 16 minutes (both in Uganda).[2] Because of this wide range of lesson duration and because the duration of literacy lessons differed among the four countries, we calculated the number of modifications each teacher made in 30 minutes. We also weighted the modifications. Content additions, content omissions, and structural changes were all coded as one modification, skipping a partial activity was weighted as 2, and skipping an entire activity was weighted as 3.

Figure 6 shows the results of the fidelity analysis, by teacher and country. Across all countries, we observed 15.9 modifications per 30 minutes of lesson time. Teachers in Uganda made the most modifications: 24 modifications per 30-minute lesson. In Ethiopia, teachers made 14 modifications, Malawian teachers made 13 and Kenyan teachers made 11 modifications on average. Kenya had less in-country variation in the number of modifications, whereas in the other three countries, the results varied widely.

Quality

To estimate the quality of the lessons observed and determine a quality proxy, we examined whether the modifications that teacher made were positive, negative, or neutral. We conceptualized quality as the percentage of modifications that the teacher made that were negative modifications.

Our results showed that most (59 percent) of the modifications made were negative. Approximately one quarter (26 percent) were positive, and only 16 percent were neutral. The prevalence of negative modifications suggests that improving teachers’ guide fidelity might help ensure improved lesson quality. Figure 7 presents the quality of the lessons by country.

The results of the modification analysis were interesting when compared among countries. Most of the modifications we observed in Uganda (74 percent), Ethiopia (65 percent), and Malawi (50 percent) were negative, whereas in Kenya, only 24 percent of the modifications teachers made were negative. We found more variation in Uganda, Ethiopia, and Malawi than in Kenya, as Teacher 6 in Malawi (M6) made fewer modifications than the average number observed in Kenya. In short, in Uganda, we observed a large number of negative modifications (meaning lower-quality lessons); in Malawi and Ethiopia, we saw some negative modifications (i.e., medium-quality lessons); and in Kenya, we observed the fewest negative modifications (i.e., higher-quality lessons).

Fidelity and Quality by Country

Based on the quality measures derived from Figure 7 above, we rated each lesson. A high-quality lesson was one that involved less than 34 percent negative modifications, a medium-quality lesson included between 34 and 66 percent negative modifications, and a low-quality lesson had more than 66 percent negative modifications. On average, using this metric, the lesson observations in Kenya were rated as high quality, those in Malawi and Ethiopia received a medium-quality rating, and those in Uganda were rated as low quality. Within each country, observed lessons ranged from high to low quality.

Figure 8 plots fidelity to the teachers’ guides on the y-axis (measured as the number of modifications made per 30 minutes) and quality on the x-axis (measured as the percentage of negative modifications). Each dot represents one classroom observation. Kenya, Malawi, and Ethiopia were all similar in terms of fidelity to the lessons. Uganda had low fidelity and relatively low quality. Note that the comparisons are all relative; that is, Kenya’s lessons were classified as high quality simply because in terms of this metric, they were of higher quality than those in Ethiopia, not because they were determined objectively to be high-quality lessons.

Types of Modifications Made in Lessons

Table 3 lists the five types of instructional modifications we expected and descriptions for each. We based the codes on categories that emerged during analysis of classroom observation data from the study in Malawi (Mattos & Sitabkhan, 2016).

Figure 9 presents the percentages of modification types by modification effect. Most of the structural modifications did not positively affect learning. Content additions tended to be positive or neutral, but content omissions were largely negative. Finally, the activity-skipped categories, both full and partial, were overwhelmingly negative.

To facilitate understanding of what these changes mean for the quality and fidelity of teaching, we present examples.

Partial Activity Skipped

Partial activity skipped modifications were negative 99 percent of the time; indeed, the teacher often skipped a part of an activity that was integral to the lesson. Table 4 lists examples of the partial activity skipped code observed in classrooms. Teachers lowered student engagement by skipping parts of the lesson in which students were to be the most engaged, such as the “You do” section activities.

Content Additions

Most of the content additions described in the classroom observation data in Table 5 tended to be positive or neutral, as teachers were adding content to enhance an activity, or to ensure extra practice. We observed some cases of negative content additions, usually when teachers added content that was irrelevant to the activity at hand, or lengthened an activity inappropriately.

Teachers made content addition modifications for a range of reasons. Some teachers’ overall lessons were not adversely affected (22 percent), and in some cases (43 percent), a lesson was improved by a content addition. Recall, however, that content additions represented a relatively small proportion of the modifications overall.

Content Omissions

In contrast to content additions, most content omissions (64 percent) were negative, because teachers were removing content that was integral to the lesson. Examples of these negative modifications are found in Table 6.

Structural Modifications

Content additions and omissions were easy to understand but structural modifications were somewhat more complicated. These changes altered the structure of the lesson, such as the direct instructional model (“I do, We do, You do”), and affected the level of student participation in an activity. Given that 51 percent of all structural modifications were negative, these changes sometimes lowered student participation. Consider an observation from Malawi, during which the teacher was teaching an activity about how to read a dialogue.

The teacher presented the activity’s content and read the dialogue to the children, as presented in the teachers’ guide (“I do”). Then, she read the dialogue with the children (“We do”). The teacher’s guide then asked her to assign roles to the students to act out the dialogue in small groups (“You do”). Instead, she simply had the students read the dialogue together as a class. In this example, the teacher modified how the content was delivered to the students and removed the group-based additional practice.

Thirty-one percent of the observed structural changes were positive. In a lesson in Uganda, the teacher was instructing students in a “before reading” activity (presented in Figure 10), from a Luganda lesson (Term 2, Week 2, Day 1). During this prereading vocabulary activity, the teachers’ guide instructs teachers to use a finger to point to the words while reading aloud. During the lesson, the teacher asked the children to use their fingers to follow along and point to the words as they were being read. Although this instruction was not specifically mentioned in the guide, the teacher helped the students engage directly with the content in their books rather than simply having them follow along with the content written on the chalkboard. Thus, the teacher increased student engagement.

Modification Patterns, by Country

Figure 11 shows the frequency of each type of modification, by country. Kenya and Ethiopia had the most structural modifications, at 63.9 and 53.0 percent, respectively. For Malawi, content addition modifications were the most prevalent (46.7 percent), whereas in Uganda, the most frequent modification was partial activity skipping (37.8 percent). These results indicate that while Kenyan and Ethiopian teachers were focused on changing the structure of the lessons, Malawian teachers tended to add content, and Ugandan teachers, disturbingly, skipped parts of activities. In Kenya, Malawi, and Uganda, we observed few instances of full activity skipping, whereas the number was higher in Ethiopia (14.5 percent of all changes).

The quality of these changes differed greatly across projects. Most of the structural modifications in Kenya were judged to be positive. For example, a teacher in Kenya asked students to discuss a picture that accompanied a read-aloud story and then to tell the teacher what they saw in the picture. This increased student participation. In Ethiopia, structural changes were largely negative. For example, during a blending activity, a teacher did not ask the students to do anything individually or with partners, as directed in the teachers’ guide, and instead conducted the activity with the whole class.

In Malawi, we observed the greatest number of content additions. For example, during a writing activity, the teacher being observed brought in a bicycle to help children understand a vocabulary word. Uganda and Ethiopia had the highest numbers of full and partial activities skipped, which negatively affected quality and fidelity scores, because almost all full and partial activity skipped modifications were negative.

Teacher Interview Findings

After we observed the teachers, we interviewed them. The interviews were conducted by two researchers: a project staff member who spoke the primary language of the teacher and a member of the research team. Using an interview protocol, we asked the teachers a variety of questions concerning their use of and perspectives on the teachers’ guide.

Was the Lesson Plan Easy to Follow?

One interview item asked whether the lesson plan in the teachers’ guide was easy to follow. Teachers across all four countries largely responded that the teachers’ guide was easy to follow or use (Table 7). In Kenya, all the interviewed teachers agreed that the teachers’ guide was easy to use because the guide was broken into steps and included everything needed to teach the lesson. One teacher noted, “Yes. Explains all of what you are supposed to do, gives you how to pronounce the word, so it is easy. Gives how the sounds are pronounced. I Do/We Do is interesting.”

In contrast, in Uganda, only half of the eight interviewed teachers said the teachers’ guide was easy to follow. Ugandan teachers who said it was difficult to follow were concerned that the lesson had too many steps, the activities were not all in one place, and the lessons scripts for the Luganda teachers’ guide were not in Luganda but in English. One teacher said, “They are not easy. They tend to be so many (steps). Looking for Literacy 2 instructions elsewhere in the teachers’ guide, now that I have taken time in the training, now I am somehow used to it.” The teachers’ guide for Uganda likely was the least straightforward of the ones analyzed for this study, in that teachers were required to look in different places within the guide to find all the parts of the lesson.

Activities Teachers Found Difficult to Teach

We asked teachers what activities they found most difficult to teach. Across all four countries, teachers noted that writing and comprehension were the most difficult activities for them and their students. Teachers who mentioned writing as the most difficult cited students’ lack of skills, such as putting words together to make sentences, or said that the children did not know how to spell. The comprehension activity that was mentioned as being particularly difficult was the prediction activity. Prediction activities are prereading comprehension exercises whereby the teacher asks the students to make a prediction about the story based on the title or a picture to help activate background knowledge. If implemented well, this will increase reading comprehension. Teachers said that this activity was difficult because students could make a prediction that was “incorrect.” One Ethiopian teacher said, “Prediction and pre-listening was hard because the prediction might be correct or not. If a pupil is wrong on the prediction, she could mislead them [the class].” The teachers seemed to misunderstand the purpose of prediction, and as a result, they considered it to be particularly difficult.

Five Malawian teachers mentioned whole-text reading as the most difficult activity. Most of these teachers explained that students either had not had enough experience in their preprimary classes or did not yet know how to read. This reaction seemed to be related to their perception of the level of their students. Given that the classroom observational data showed that many Malawian teachers were making structural changes to the lessons to reduce the amount of time that children were reading, this perception of reading being too difficult for children reduced the opportunities for Malawian children to read.

The interviewed Kenyan teachers found the vocabulary activities problematic. One teacher explained, “Vocabulary. It is not very easy to make a sentence using that word and for the meaning to come out. Some of the words are hard.” These activities were the least explicitly scripted activities in the Kenyan teachers’ guides. The Ethiopian teachers were evenly divided in their opinions among the types of activities, although more teachers noted that the comprehension activities were difficult to teach.

Formatting

The interviewers also solicited teachers’ responses as to how to improve the teachers’ guides. Several ideas were shared (see Table 8). Changing various aspects of the teachers’ guide formatting was discussed in interviews with Kenyan teachers primarily. The Kenyan teachers were concerned with having everything on one page, including the time for each activity and the vocabulary definitions. They also wanted their teachers’ guide to be printed in color.

“Should include the time for each activity in the lesson within the teachers’ guide (rather than only in the front matter table). Put the meanings of some words either in the lesson plan or front matter.” − Kenya teacher

Most of these suggestions would have implications for easing the burden on teachers to understand the teachers’ guides. Interestingly, teachers in the countries with lower student performance outcomes had fewer concerns about the formatting of the guides. This finding could suggest that teachers were overwhelmed with struggling students and needed the guides to provide more strategies for how to support these students. Paradoxically, incorporating more structures would add to the complexity of the teachers’ guides.

Advice for Helping New Teachers

The interviewers asked teachers to give advice on what new teachers would need to be successful with the teachers’ guides. Ethiopian teachers were concerned with preparing adequately (25 percent), following the teachers’ guides (50 percent), and teaching teachers to use the guide (25 percent). Kenyan teachers said that new teachers should be told to follow the teachers’ guide, apparently believing that doing so would lead to better instruction.

“The teachers’ guide has full script lessons so that they get used to it, to carry on to the short script. Full script follows step by step and allows you to get used to it. They will be able to teach the lessons.” − Kenya teacher

Most Ugandan teachers (70 percent) said that teachers should be taught the mechanisms and complexity of how to use the Ugandan teachers’ guides. These guides contained activity scripts for Literacy 1 and 2 lessons in one location and the content in two different locations in the guide. Therefore, these teachers felt that being proficient at gathering all the necessary information was important. Half of the Ethiopian teachers (50 percent) also mentioned teaching teachers to use the guide. Their guide sometimes required teachers to look back a page or two for stories.

“Teach them how to use the teachers’ guide. Can sit together with them, do a scheme of work, and a lesson plan. Then I would have them sit behind in the lesson and teach. Show them how to use the teachers’ guide, by reading together, showing the steps.” – Uganda teacher

Explaining Modifications

The teachers were asked about three to four modifications that they made in the lesson, including why they deviated from the lesson plan. Disappointingly, 25 percent of the Ugandan teachers interviewed noted that their modifications came because they had forgotten about an activity. This response was most frequently given in Uganda, possibly because of the aforementioned issue in which teachers had to look at different parts of the teachers’ guide to gather all the information they needed. In Malawi, which had the next highest percentage of teachers who forgot parts of the lesson (10.3 percent), the teachers were trained to use lesson notes rather than the guide. They noted that the guide itself was quite heavy, and they preferred the lesson notes. We found that, in Malawi, much instructional guidance was lost in the transition from the teachers’ guide to lesson notes. Teachers in Ethiopia had the fewest instances of forgetting parts of the lesson (4.8 percent).

Student Needs

The most frequent explanation for a modification was related to the students’ needs. The teachers modified their lessons because they were concerned that at least some students in their classroom were not academically ready for the lesson.

Teachers in Ethiopia (70.0 percent) and Kenya (42.9 percent) were mainly concerned with their students’ understanding of the content. Ethiopian teachers tended to leave out sections of lessons because they did not believe their students would understand. In the following example, the teacher skipped multiple activities:

Ethiopia teacher

Modification: Did not do reading, word study, or writing

Explanation: Afraid they don’t understand if I don’t teach it all like this. Information is too much for them. They understand from repeating for them to understand.

In Uganda, teachers changed an activity to provide feedback to students; in Malawi and Ethiopia, teachers were more likely to add support such as reading with students instead of letting them read on their own. For example, the Malawian teacher quoted below did not believe that her students could read on their own, but she thought it would help to let them read in groups with her. However, this approach seemed to lead to students not actually reading but instead echoing what they heard.

Malawi teacher

Modification: Learners reading at the table in groups

Explanation: I wanted learners to read with me. Some learners were not able to read the words; they were waiting for the teacher to read them the word. They wait for me to revise [review] the word, and then they read.

The third most common explanation for modifications was teachers’ concern about their students’ academic level. Teachers in Kenya (28.6 percent), Malawi (28.6 percent), and Uganda (33.3 percent) seemed to make changes to the lesson because they did not believe their students had enough knowledge to accomplish a certain task. In Kenya, one of the teachers interviewed did not want to discuss any student predictions that she knew would not come true. Because the students did not yet know how to predict, she found it easier or more useful to focus on the students who got the answer “correct.”

Kenya teacher

Modification: Didn’t discuss the predictions that did not come true, only discussed those that were proven true in the story

Explanation: Prediction is not easy, as they do not know how to predict.

Recommendations

Given the findings from the teachers’ guide study, we offer the following general recommendations. In addition, RTI International has developed specific guidelines on materials development that we share in Tables ES-1 and ES-2.

-

Encourage lesson fidelity. All teachers using lesson plans made modifications to those lesson plans. Given that most of these modifications (59 percent) negatively impacted the quality of the lesson, more should be done to support teachers in understanding the activities in each lesson and to encourage the teachers to use the instructional methodology.

-

Reduce the wordiness and bulkiness of some of the teachers’ guides. Efforts should be made to simplify materials and reduce scripting to better support teachers in making both fewer negative modifications and more positive ones.

-

Put instructions and content in one place in the lesson, using the same language. The Ugandan teachers we observed made the most modifications and had the highest percentage of negative modifications (68 percent). Teacher interview data suggested that this was partly because the lesson plan directions and corresponding content were in different places in the guides, and the lesson plans and directions were presented in different languages.

-

Emphasize the importance of group work and practice in training and coaching. Many of the modifications that teachers made altered the structure of the lesson. When these modifications were negative, they often decreased student participation. When planners are developing materials and teacher trainings, they should emphasize the importance of independent work and group practice.

-

Keep it simple. The teachers’ guides should be simple, with limited amounts of scripting, provide teachers with everything for a lesson in one place, with easy-to-follow instructions.

-

Consider reducing the amount of content and number of activities. It may be helpful to consider the amount of content and number of activities included in the lessons, especially for countries such as Malawi, where student-to-teacher ratios are extremely high and where teachers may have lower capacity and less experience.

-

Remove the responsibility for developing lesson plans or lesson notes from teachers. We encourage programs to work with governments to remove the expectation of developing lesson plans and lesson notes until instructional quality improves, and meaningful differentiation is possible.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the RTI International Chiefs of Party working on international education projects who conceptualized the study, the project staff that supported the research, and the participating teachers in Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi and Uganda. We are thankful for Melinda Taylor’s support for this research study, and we appreciate the excellent editorial work of Erin Newton and Amy Morrow. We appreciate the technical expertise of the experts who developed the teachers’ guides, including government counterparts, RTI project staff, and materials development experts, especially SIL LEAD who provided quality technical assistance in the development of these materials in many countries. We appreciate the technical expertise of the experts who developed the teachers’ guides, including government counterparts, RTI project staff, and materials development experts, especially SIL LEAD, who provided quality technical assistance in the development of these materials in many countries. This study was supported by an Institutional Research & Development research grant from RTI International.

Impact evaluation results were available for Kenya Tusome (Freudenberger & Davis, 2017), Liberia EGRA Plus (Piper & Korda, 2011), Ethiopia READ (American Institutes for Research, 2016; RTI International, 2014a), Kenya USAID PRIMR (Piper, King, & Mugenda, 2016), Egypt Girls’ Improved Learning Outcomes (GILO) (RTI International, 2012), Uganda SHRP (Brunette et al., 2017), Kenya DFID PRIMR (Piper, Zuilkowski, & Ong’ele, 2016), Malawi EGRA (Jere, Orr, Bisgard, & Ogawa, 2015), South Africa IEP (Piper, 2009), a Jordan Education Data for Decision Making (EdData II) task order that preceded Jordan RAMP (Brombacher, Stern, Nordstrum, Cummiskey, & Mulcahy-Dunn, 2015), Nigeria RARA (RTI International, 2016), Liberia LTTP2 (King, Korda, Nordstrum, & Edwards, 2015), and Haiti ToTAL (RTI International, 2014b).

Evidence suggests that both shorter and longer lessons are evidence of poor implementation. Given that the teachers selected were identified based on the quality of their teaching, it is certainly concerning that these lesson lengths deviated so far from the expected time. Typically, this level of variance suggests a lack of comfort with the lesson activities or a reduction in the number of activities followed.

__by_teacher_and_by_country_average.jpg)

__by_teacher_and_c.jpg)

_affected_by_a_positive_structural_modification.jpg)

__by_teacher_and_by_country_average.jpg)

__by_teacher_and_c.jpg)

_affected_by_a_positive_structural_modification.jpg)