Introduction

In the United States, we like to think of education as the great equalizer. Decades of data, however, indicate that our education system is failing to meet that ideal for a significant portion of the US population. Over the years, institutionalized policies and practices have resulted in persistent disparities in education for nondominant students of color. We use the term “nondominant” to identify students and communities who are excluded by our nation’s school system through the privileging of certain cultural, social, and economic norms. For example, school systems systematically prevent marginalized students from accessing advanced courses (Kolluri, 2018), and school staff place Black, Indigenous, or Latinx students in special education at high rates, resulting in their overrepresentation (Office of Special Education Programs, 2020). Black students are more likely to be viewed as disruptive and more likely to be suspended for the same behavioral disruptions as their White peers (Riddle & Sinclair, 2019).

The collective policies and practices that marginalize nondominant students also lead to disparities in educational outcomes. For instance, Pearman et al. (2019) indicate that discriminatory disciplinary practices are correlated with poorer academic performance, especially for Black students. Additionally, Black, Latinx, and Indigenous students on average score disproportionately lower on standardized reading assessments (National Assessment of Educational Progress, 2019) and have disproportionately lower high school graduation rates (McFarland et al., 2019). These disparities are the result of an education system rooted in systems of colonialism and White supremacy, which American schools were designed to reproduce and maintain (Spring, 2016; Valenzuela, 1999). With institutionalized racism “enmeshed” in the school system’s policies, practices, and mindsets (Ladson-Billings, 1998, p. 11), American schools will continue to produce inequitable outcomes for students and communities on the margins of society’s dominant norms, beliefs, and values.

In the education sector—as well as others, such as health, justice, and finance—policies, practices, and mindsets often reflect unconscious and inaccurate assumptions based on race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Psychologists refer to these unconscious attributions as unconscious or implicit biases, which are the consequence of an immediate and automatic information processing and decision-making system that is sometimes necessary for survival (Kahneman, 2011). Because these automatic attributions are shaped in part by our societal context, they can integrate stereotypes and other inaccurate assumptions about others without our awareness. In the United States, where dominant narratives of White superiority unconsciously inform our assumptions about others (Feagin, 2013), negative and damaging narratives of people of color, especially Black and Brown communities, have a strong and often unconscious effect on our decisions and actions.

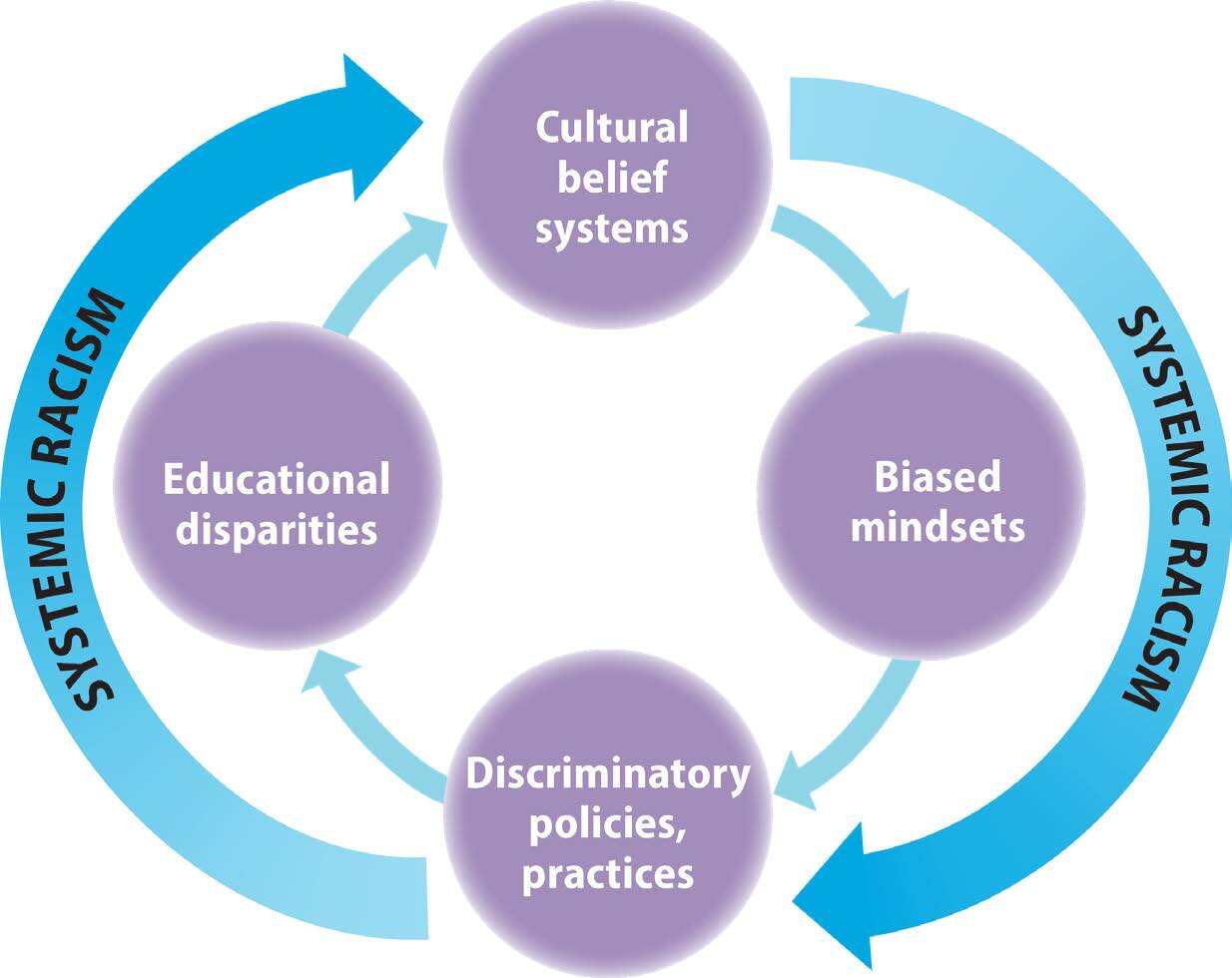

Payne and Hannay (2021) describe how unconscious or implicit biased narratives arise and are sustained in environments where systemic racism is embedded. Figure 1 illustrates this relationship and the cycle that leads to discriminatory policies and practices, which in turn lead to educational disparities. These negative outcomes reinforce biased mindsets, and the cycle continues. Without disrupting this process, systemic, institutionalized racism and educational disparities endure. In education, this cycle can be particularly detrimental because, increasingly, education is the ticket to not only economic success but also basic survival (Darling-Hammond, 2001).

Research has shown implicit biases to be a key factor in creating and perpetuating disparities in students’ experiences of schooling, learning, and longer-term outcomes, including job opportunities, wealth, and health (Darling-Hammond, 2001; Dee & Gershenson, 2017). Therefore, now more than ever, current school reform and transformation efforts are aimed at addressing institutionalized racism in school policies, practices, and cultural systems by implementing implicit bias training for teachers and staff and adding restorative justice practices to remedy some of the inequities our students are experiencing. In this paper, we summarize results of a study funded by the Flamboyan Foundation and reported in full by McKnight et al., 2017. The study documented how a school home visit program, Parent Teacher Home Visits (PTHV), can interrupt the insidious cycle of biased mindsets and lead to better outcomes for families and students. We found that the key components of these home visits align with strategies that psychological research has demonstrated to effectively counteract implicit biases and discriminatory behaviors. Additionally, we found that educators who participated in PTHV shifted their mindsets from focusing on assumed student and family deficits to their strengths and assets. These mindset shifts stimulated the use of practices rooted in empathy and understanding, which affected relationships between families and schools, school culture, and student success. On the basis of our study findings, we propose that this relational model of home visits can be an effective method for disrupting biased mindsets to help break the cycle of institutionalized racism in our schools.

How Biased Mindsets Affect Family and School Interactions

Decades of research document that educators’ expectations and beliefs, in part driven by implicit biases, are critical factors leading to educational disparities for nondominant students. These beliefs are often based in a historical tradition of “deficit thinking,” which focuses on the idea that poor student outcomes are a result of internal deficits in students or their families rather than the structural failings of the school system (Bang et al., 2019; Kim, 2009; Valencia, 2002). This type of thinking is reflected in the notion of “culturally deprived” children in the 1960s and “at risk” children in the 1980s (Valencia, 2002).

Educators’ implicit biases influence their teaching practices, recommendations for opportunities like course placement, enrichment activities, special education, and discipline, as well as beliefs and expectations they consciously and unconsciously convey to students. Research shows that positive teacher beliefs about students are associated with positive student outcomes (Goddard et al., 2001; Yeager et al., 2014), and negative beliefs are associated with negative outcomes (Dee & Gershenson, 2017; Riddle & Sinclair, 2019). Educators’ unconscious expectations and beliefs can extend to their students’ families as well, including assumptions about parents’ beliefs about the value of education (Kim, 2009; Quiocho & Daoud, 2006; Valencia, 2002). These assumptions and beliefs have led to strained relationships and mistrust between schools and the communities they serve. This is especially problematic because research indicates that positive relationships between schools and families contribute to sustained school improvement and effective teaching and learning (Bryk & Schneider, 2003). These research findings linking educators’ implicit biases, unconscious beliefs, and detrimental student outcomes highlight the need for interventions that can help to counteract these biases and beliefs. Although implicit biases are automatic and unconscious, research suggests that we can counteract them and reduce discriminatory behaviors. PTHV shows promise for doing just that.

Parent Teacher Home Visits Program

Program staff refer to PTHV as a “relational model” for home visits. Focused on grades K–12, PTHV grew from a local effort at eight schools in Sacramento in 1998 to a national network of more than 500 schools in 28 states and Washington, D.C. The program is voluntary for educators and families and involves educators visiting each student and their family at their home at least twice per year. The model focuses on promoting mutually supportive and accountable relationships between educators and families. PTHV differs from other home visit programs in that the focus is on relationship-building instead of student performance or behavior, which can reinforce prevailing power structures between schools and families and hinder relationship-building.

In PTHV, educators are trained in how to implement home visits with a focus on relationship-building, reflecting on their own assumptions about students and families, learning to build trust with families, and increasing their capacity to engage students in the classroom. Educators then visit the homes of their students in teams of two, conducting the initial visit in the summer or fall. Typically, they are compensated for visits conducted outside of their workday. The PTHV model emphasizes discussing hopes and dreams educators and family members have for students and sharing information about themselves. Communication continues after the first home visit, enabling teachers to apply what they learned about their students to instruction and encouraging families to engage more fully with the school and their child’s coursework. A second visit in the winter or spring focuses on academics, with reference to the hopes, dreams, and goals shared in the first visit. Although the way schools implement the home visits varies, all schools agree to five core components:

-

Visits are always voluntary for educators and families and arranged in advance.

-

Teachers are trained and compensated for visits outside their school day to demonstrate value and respect for the time they commit.

-

The focus of the first visit is relationship-building; educators and families discuss hopes and dreams.

-

There is no targeting; visits are for a cross-section of students, so there is no stigma attached.

-

Educators conduct visits in pairs and, after the visit, reflect with their partners.

Our Research Study

In 2017, we conducted a study of PTHV in which we aimed to understand whether and how this relational model of home visits affected educators’ mindsets in ways that influenced educator-family relationships and the success of students. We did not set out to measure implicit biases, because they are unconscious by definition and notoriously difficult to measure. Instead, we focused on explicit mindsets that educators could articulate and how those may or may not have changed over the course of the home visits. Eleven schools from four large districts participated. Each district had implemented PTHV for at least 5 years and was a member of the PTHV national network. They were located in four states, three in the West and one in the Northeast. The districts ranged in size from serving approximately 41,000 students to serving more than 92,000. In these schools, students of color were the majority, with seven schools serving primarily Latinx students, one serving primarily Black students, and three serving a majority of Black and Latinx students. For all but one school, 73 percent to 100 percent of students were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. In the outlier school, only 5 percent of students were eligible. In each district, we selected a mix of elementary, middle, and high schools with a wide range of experience with PTHV (ranging from 1 to more than 15 years).

We conducted interviews and focus groups with 107 educators and 68 family members who volunteered to participate across 11 study schools on-site. Focus groups with family members were separate from those with educators. This design was intended to help avoid power dynamics and social pressure that could influence results. Of the 107 educators, 20 (18.7 percent) were school staff other than teachers (for example, counselors and instructional coaches), all of whom had conducted home visits. For those who taught in classrooms, the average number of years teaching was 11.3. The average number of years participating in PTHV was about 3 (with four educators who had not yet participated), and the number of visits ranged widely, from 1 to more than 1,200. Educator race and ethnicity data were available for four of the 11 schools, where 40 percent to more than 90 percent of educators were people of color.

We used semistructured interview and focus group protocols to ask a series of questions about participants’ experience with PTHV. We asked educators whether and how their attitudes and beliefs about students’ families had changed after home visits and what aspects of the visits influenced these changes. We asked family members how, if at all, the visits improved their relationships with educators. We asked both groups about changes in behaviors, if any, following home visits (e.g., other interactions with the school, adjusting classroom practices, and so on). The questions were framed neutrally to allow participants to freely share their experiences, including those that were negative, positive, or neutral. We recorded interviews and focus groups and transcribed them for coding. The study team developed a coding structure, informed by research literature on implicit and explicit biases. Multiple researchers coded the transcripts to identify common themes and evaluate interrater reliability. McKnight and colleagues (2017) describe the methodology and our findings in greater detail.

How Relational Home Visits Can Shift Biased Mindsets

In interviews and focus groups, we repeatedly heard from educators and family members that home visits helped them recognize that assumptions and beliefs they held about each other were unfounded. By visiting families in their homes and focusing visits on sharing hopes and dreams, both educators and family members reported newfound understanding and empathy for each other. Research on implicit biases indicates that a key strategy for counteracting them is through building empathy by recognizing others as unique individuals and as human beings with struggles and dreams like our own (e.g., Whitford & Emerson, 2019). Here, we share the mindset and practice shifts that the home visits invoked, according to participating educators and family members.

Home Visits Shifted Educator Beliefs and Improved Communication With Families

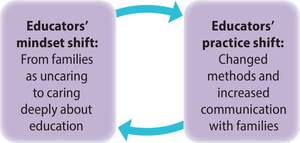

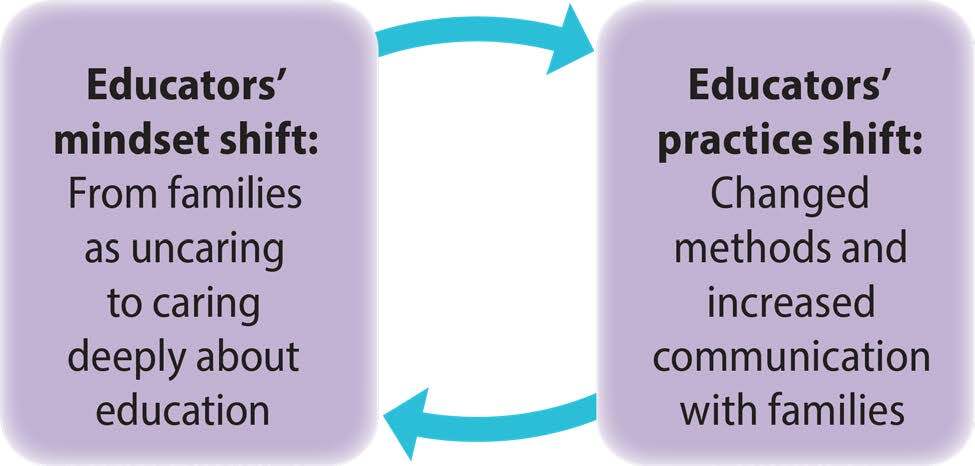

A key theme that arose from interviews with educators is that the home visits helped them shift from assuming that families were indifferent about their child’s education to recognizing that they demonstrated their care in ways that differed from what schools expected (Figure 2).

Educators learned that families were involved in their child’s education in a variety of unexpected ways and cared deeply about their child’s success. They saw that demonstrating commitment in ways that dominant families typically do was often not possible. For example, many families could not come to events at school, in the day or in the evening, because of work schedules, transportation issues, and so on. Sometimes, they did not respond to school or teacher communications because of language barriers. Before the home visits, teachers often interpreted these actions as reflecting a lack of concern about their child’s learning progress. However, the home visits showed that these families engaged in many “behind-the-scenes” ways in their child’s learning, such as monitoring reading time, scheduling or checking homework, and having their child explain what they were learning. As one teacher explained,

I expected parents to volunteer in certain roles in the school, but parents did not feel good to be involved in [school activities]. If they feel limited in skills, they won’t go into the classroom. Maybe they can participate in different ways. In the past, if a parent was not signing up to volunteer to go to the zoo, then the parent wasn’t “involved.” Family involvement is every day until they get the child to school…. Everybody cares for the child in a different way.

Educators saw the initial home visit as building a reserve of trust that they could draw on when needed. Home visits allowed them to learn the best ways to communicate with families, such as through texting, and the best person to contact. Home visits also helped them feel more comfortable communicating with family members, especially when challenging situations at school arose. Instead of dreading calls to parents about student problems, educators reframed it as building a partnership based on trust that everyone was looking out for the best interest of the child. As a result, educators could ask for family members’ advice on how to best handle situations at school. As one educator noticed,

[After home visits] when you call home, you definitely get a different type of conversation there. It’s almost like you’re having a talk with one of your neighbors…. It reminds me of when I was a kid and we’d always say, “It takes a village to raise a child.” And that doesn’t happen much now [in schools]. But it’s almost like a partnership that you’ve built with them. They trust you and they know that you’re in this partnership. So, when you do call them to tell them something, you’ve already built up such a good rapport and such a good relationship that they know your intention behind whatever it is that you’re telling them.

Notably, after home visits began, some educators reported having extended this improved communication to all families. Through home visits, they recognized that families do not always have positive interactions with school staff, and developing positive communication built strong, trusting partnerships to support students.

Educators Shifted From Deficit-Based Beliefs to Assets-Based Classroom Practices

Another key theme from our study indicated similar shifts in educators’ perceptions about students’ behaviors. Educators reported that home visits helped them develop a nuanced understanding of students’ home lives, which countered their deficit-based assumptions, especially by recognizing students’ skills and capabilities in ways that were not demonstrated at school. One educator explained an evolving understanding of how a student’s home environment impacts school performance:

What they’re asked to do at home as a 9- or 10-year-old, it’s pretty amazing. I know as a fourth grader, I wasn’t asked to do that stuff. It’s kind of interesting to know that they’re here all day and you’re trying to get them to learn and work hard but they have to go home to other family situations where they have to watch little brother, little sister, mom and dad aren’t home quite yet. As much as we may think they’re not responsible, I think in their own right, they are. They may not have their whole desk together, and their desk might be falling apart at school, but there’s probably other things on their minds. It’s pretty admirable to see them in that atmosphere.

Multiple educators shared similar observations that although students’ behavior in class may seem disruptive or problematic, it does not necessarily mean that students do not care or lack interest in learning. As one teacher explained,

There’s a kid that has a baby sister at home, and mom has to work late, so as a third grader his responsibility is to take care of her. That takes a lot of their time from being a kid…. It helps you understand that’s probably why he’s sluggish. It’s not that they don’t want to be here. It’s not that they don’t want to learn. They have a whole other life outside of the school going on.

Despite reporting a better understanding of students and families after participating in home visits, a small proportion of educators maintained their deficit perspectives of families to explain student behaviors. They continued to negatively frame student behaviors like absenteeism, missing homework, or acting out if they failed to align with traditional expectations. Furthermore, some continued to attribute those behaviors to family shortcomings such as lack of resources, living environment, and parenting style.

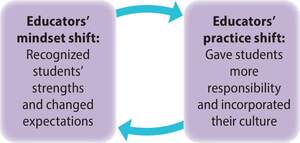

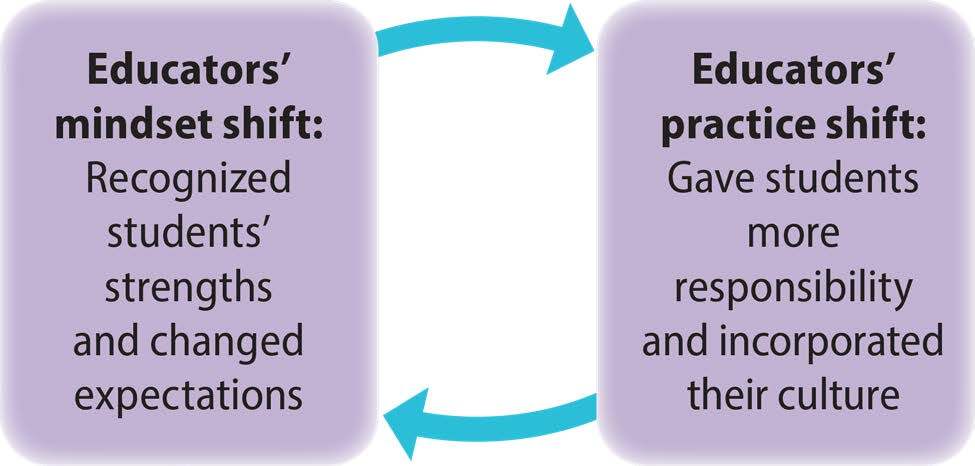

Another key theme that arose from interviews with educators was how an improved understanding of the child and their home life, culture, and unique capabilities helped shift teaching practices to an assets-based instructional approach (Figure 3). This approach demonstrates an understanding of students and families, recognizes their strengths and cultures (Ladson-Billings, 1995, 2014), and prioritizes those strengths over perceived shortcomings or failures (i.e., deficit thinking). An assets-based approach incorporates students’ cultural, language, and life experiences into teaching practices. Also known as culturally responsive teaching, this approach is a strategy by which school systems can mitigate the decades of harm inflicted on nondominant students and their families (Ladson-Billings, 1995, 2014).

Our study results suggest that as educators developed an understanding of students’ interests and capabilities, they attempted to draw on these in the classroom. For example, one educator described an attempt to motivate a student to help in class based on how that student helped with brothers and sisters at home:

So, I had one student who was a pretty big goofball in class…. He didn’t really do his work. He didn’t really take anything seriously. And then when I did a home visit, he showed that he really took his little brother seriously. He took care of his little brother a lot. We were in the home visit and his little brother was throwing this ball at me…[and he said], “Hey you can’t throw balls at people while they’re having a conversation.” … So this kid is a leader at home. I was able to start to guide him toward doing that same thing in the classroom…. We could talk about how he shows leadership at home and how he can show leadership in the classroom.

Educators also reported connecting instructional activities in the classroom to students’ home lives. Home visits helped teachers choose books and writing assignments aligned with interests their students showed at home. One teacher explained how knowing students’ backgrounds was critical to helping build their connection to texts, which is why they felt that home visits were crucial. Another explained how building this connection between home and school increases motivation for learning:

So, if I know that their dad works in construction…when we’re talking about area and perimeter, we can talk about, when you’re building a house, you need to make sure you’re measuring accurately. And then you need to calculate the square footage of a floor to be able to figure out how much flooring you need…. And they’re like, “Whoa! My dad uses this. Maybe I should actually learn this.”

Research on student motivation and engagement suggests that incorporating students’ personal interests in the classroom can trigger passion for learning, which leads to improved academic behaviors (Deci et al., 1991, 2001). Incorporating students’ personal interests in the subject matter can also result in their deeper conceptual understanding of the content (Deci et al., 1991, 2001).

Home Visits Fostered Educators’ Empathy and Changed Punitive Practices

Through learning about students’ home lives and seeing them in a different environment, educators developed deep empathy for students and their families. Although our study design does not allow us to draw a causal link between home visits and changes in implicit biases, psychological research indicates that building intergroup empathy is a critical mechanism by which implicit biases can be counteracted. In our study, educators identified developing empathy because of their interactions with students and families in their homes. One teacher emphasized that the empathy she developed for a student she visited was “100% without a doubt” the result of home visits: “Because…until you see [kids] in their own environment, you don’t really know.” Because of that empathy, teachers changed practices and policies aimed at students and families, particularly around disciplinary actions (Figure 4).

For example, one educator reflected,

It gives me a lot of patience…. I know when I was doing home visits with third graders, I had a student [who wore my patience thin]. To see him at home, and he was just the sweetest gentleman…offering me water, and closed the door because the dog was barking, and to see him at home with his family, I had never-ending patience for him after that. Because I had been with his family and seen him as the person, this sweet little boy that his parents see him as.

Relatedly, educators explained how empathy had affected their disciplinary reactions, exemplified in the following statement:

Instead of being frustrated, I can step back and go, “Okay, how can we rework this?” [It’s] patience that you would have for your own child.

Similarly, another teacher observed,

I can be like, “So, what’s going on? How’s this going? Is there a way that I can help you to find time to do your homework? Can we get you an afterschool program? Here’s some resources that your mom can use, send her to the community liaison office to get resources for legal issues.”

Educators also changed how they handled situations with students during the school day. When home visits indicated challenges at home, such as the health of a grandparent, educators could reframe the classroom situation and respond with empathy by asking how things were at home. Several also changed punitive classroom policies around late and incomplete homework after conducting home visits, choosing to focus on why students were struggling rather than penalizing them.

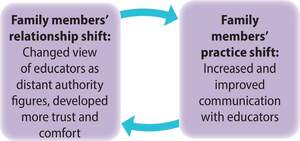

Families Increased Trust and Comfort With Educators

Focus groups with families yielded similar findings about changed assumptions about educators. A key theme was that home visits helped families realize that interactions with educators did not have to be negative or uncomfortable, which helped the families develop strong and equitable relationships with school staff. Most families reported that their perceptions of educators changed from distant authority figures to people to whom they could relate. As a result, families reported increased confidence in reaching out to educators and communicating about students’ needs (Figure 5).

A good proportion of families reported that when scheduling the first home visit, they feared the school’s motives and doubted that the intended purpose was to get to know them. Many feared that home visits were instead akin to social service visits, focused on assessing the quality of home life, parenting styles, or that they lived within school boundaries. They expressed surprise after the first visit that the interaction was positive and, moreover, that educators seemed to care about them and their students. As one parent explained,

Well, when she came, I ain’t going to lie, I cleaned up…. Scrubbed my walls, scrubbed my floors, lit the incense. I even made dinner for her, and she ate it! I was shocked. And she don’t even eat green beans and she ate mine! That broke down the wall when I [saw] her do that…. And she was like, “Oh I see that you guys are photogenic, you got a lot of pictures on your wall.” And I was like, “Okay, she cool.” You know, and then after that, we just was like “this” [crosses fingers].

Before home visits, families viewed educators as distant authority figures of higher status. Home visits enabled them to see them as human beings, as equals. Before the visits, families often felt too intimidated to speak with educators. For example, one family member initially rejected the home visit because they had not graduated high school and feared that the teacher would come into the house speaking “big words.” Focus group data indicated this was a common fear, and it changed after the home visit. Families saw educators as “normal” and as “human beings,” and reported feeling less “afraid” of talking with and trusting them. In research on implicit biases, seeing people as “other” helps to distance them, creating “in-groups” and “out-groups,” which can lead to stereotyping and discriminatory behaviors. Strategies that help people see the “other” as human, like themselves, are particularly powerful for counteracting those biases.

Families Improved Communication With Educators

After home visits, families felt more comfortable communicating with teachers and, as a result, did so more frequently. Their newfound perceptions of teachers as equals, and even as friends, increased confidence in sharing information without fear of judgment. They expressed trust in teachers. One family member explained what this change looked like and why it happened:

At first there was no communication with the teacher, it was drop off, pick up, and see you later. But now if I have any question, I feel more comfortable to talk to [the teacher]…. If the teacher needs to communicate with me, it feels like the home visit broke the ice between us. So if there is any doubt or problem, it’s easier for me to communicate with the teacher.

Families reported feeling comfortable approaching educators to discuss students, including asking for help and confiding about situations at home. In general, they attributed their increased confidence to the developed trust in them. One family member explained,

It’s easier to sit down and talk to her because now it’s like, “Oh, I don’t have to worry about the image of that teacher, that authority kind of thing.” Now she’s down-to-earth and we can actually be completely honest with each other versus trying to talk to this person and cover up what’s really going on. It’s a whole lot different. It breaks down the barrier.

Families related being more comfortable sharing information with educators, such as explaining students’ incomplete homework or asking for feedback on students’ behavior—for example, because of a father’s recent incarceration—compared with before the home visits. One parent reported opening up to their child’s teacher:

When I finally had the meeting with the teacher at my house, I explained to her that [the student] would miss school several days. Not because I didn’t want to take her to school but because she had health issues. The teacher was surprised and said…if I had told them they could have helped…. So it’s a deeper relationship, where you trust her and you say, “I feel this way. I’m worried about my kid. Could you observe my daughter?” … If you don’t trust someone, you can greet them, you can see them, but you won’t open that door beyond that.

Families also reported positive change in students’ behavior and academic performance and attributed it to improved communication with their teachers. As one parent explained,

In kindergarten, I was not visited, and my child was falling behind, and because of that I didn’t understand about the homework and what had to be done, and I didn’t know how to help her. After the visits every year, I’ve been more open to ask questions: “How can I help my child and continue to push her?” I think that she is doing better in class, and I think it’s because of the communication with the teacher.

Overall, families realized that interactions with educators could be positive. Many shifted their perceptions of educators as distant authority figures to people they could relate to and trust. Some described their children’s teachers as a “friend” or “family member” after the home visits. As a result, they were confident in reaching out to educators, communicating students’ needs, and trusting that they would be heard and respected.

How Parent Teacher Home Visits Aligns With Research on Counteracting Implicit Biases

The PTHV model did not start as a program explicitly designed to shift biased mindsets and address inequities in education systems. Yet as program staff noticed that home visits appeared to bridge divides between families and schools caused by race, culture, language, and socioeconomic status, they hypothesized that this “bridging” was an essential component of the program’s impact. Our study set out to test this hypothesis through interviews with educators and family members participating in PTHV and a review of research on implicit and explicit biases. The themes that emerged from interview data suggest that the PTHV model and its core practices align well with research-supported strategies for reducing implicit biases and discriminatory behaviors, beyond building empathy between families and educators. Table 1 highlights research-supported strategies for counteracting implicit biases and ways the PTHV model aligns with those strategies.

Table 1 shows how the PTHV model engages multiple strategies to build strong, trusting partnerships between families and educators, where race, culture, language, and socioeconomic status have historically served as barriers. These strategies have a research base that suggests they are effective at counteracting implicit biases, building positive intergroup relationships, and reducing discriminatory behaviors.

Limitations to Our Study

Our research approach involved gathering self-reported perceptions of individuals who participated in PTHV to understand the impact on mindsets and practices related to supporting students and their families in their educational success. The scope of this work did not allow us to verify the reported changes with other sources of data, such as classroom observations or documented interactions between families and educators. However, the patterns presented in this report are from 68 family members and more than 100 educators across different school and district contexts. We also did not measure implicit biases, which are notoriously difficult to measure and can create anxiety and stress among study participants who fear that they may be categorized as “racist” because of these assessments. Therefore, we focused on self-report and self-perceptions to help ensure that families and educators would participate in the study and feel safe doing so. Additionally, participation in the study was voluntary. It may be that those who agreed to participate had the strongest opinions about PTHV and may not reflect all family members’ and educators’ experiences. We tried to mitigate barriers to participation in the family focus groups by providing food, childcare, and flexible times for the interviews.

Conclusions

From our research with educators and families and our review of the literature on implicit biases, we suggest that relational home visits can disrupt the process by which biased mindsets lead to discriminatory practices and inequitable educational outcomes. Home visits focused on relationship-building can help shift educators’ deficit mindsets about families and students in ways that support the implementation of asset-based teaching practices and strong partnerships with families, both of which are linked to improved outcomes for students. In a separate and methodologically rigorous study of schools implementing PTHV, Sheldon and Jung (2018) found that schools that implemented PTHV had lower rates of chronic absenteeism than schools that did not implement PTHV. Additionally, students who attended schools that conducted home visits were 1.34 times more likely to score proficient or better on standardized English Language Arts tests than those who did not attend such schools.

Our research focused on individual mindsets and practice changes, not on school- or district-wide policies, practices, or mindset shifts. Yet Sheldon and Jung’s (2018) findings suggest that implementation of PTHV can affect all students, not just those who directly participate in home visits. Students who attend schools that conducted home visits with at least 10 percent of their students seemed to benefit indirectly from this program. It may be that when multiple teachers at one school conduct home visits, their experiences can help create a culture shift from persistent deficit narratives about students and families. This shift may then lead to school-wide policies or programs that are more aligned with asset-based values and beliefs. Further studies are warranted to explore this link between school-level implementation, school culture, and policy and practice shifts that can help change inequitable experiences and outcomes in our nation’s schools.

PTHV leverages multiple research-supported strategies that reduce implicit biases. However, to make a sustainable impact on institutional racism in our nation’s education system, PTHV should be one of multiple interventions designed to change widespread discriminatory policies and practices. As noted in our study, some educators maintained deficit perspectives of families despite participating in PTHV. Other research-based approaches such as critical dialog, reflective journaling, cognitive debiasing techniques, role-playing, and perspective-taking can also help reduce implicit biases and foster positive intergroup relationships. School and district leaders should consider PTHV as one of multiple effective tools in their toolbox to disrupt and eliminate the pernicious effects of systemic racism that undergird many of our nation’s school policies and practices.

Acknowledgments

We thank the educators and family members who shared their experiences of the Parent Teacher Home Visit (PTHV) program with us. We also appreciate the strong dedication of PTHV and Flamboyan Foundation staff to the evaluation.

RTI Press Associate Editor: Jules Payne