The racial and socioeconomic targeting of incarceration has made it a common rite of passage for young men and their intimate or co-parenting partners in many urban communities (Comfort, 2012; Lopez-Aguado, 2016; Sampson & Loeffler, 2010; Western & Pettit, 2010; Western & Wildeman, 2008). Men are 13 times more likely to be incarcerated than women (Carson & Anderson, 2016), but women are heavily affected as well—particularly through relationships with imprisoned and formerly imprisoned men, which one in five American women has experienced (Enns et al., 2019).

We conducted research on these relationships as part of the Multi-site Family Study on Incarceration, Parenting and Partnering (2006–2016; referred to hereafter as the “Multi-site Family Study”). Fully half of study couples reported physical violence during the 6 months after the male partner’s return from prison (McKay et al., 2018). Those who are involved with the criminal justice system (whether directly or through a family member’s involvement) may be particularly reluctant to disclose their experiences or seek help for partner violence because of learned distrust of institutions or concerns about exposing their partners or themselves to further punishment (Coker & Macquoid, 2015; Hampton et al., 2003; Mehrotra et al., 2016).

Examining Partner Violence Help-Seeking: The Post-Incarceration Partner Violence Study[1]

The decision not to access support can have serious consequences, particularly for victims with few resources for whom safety is often unattainable without outside help (Velonis et al., 2017; Zapor et al., 2018). However, help-seeking among couples affected by incarceration (and the unique barriers that may prevent it) is poorly understood. Responding to this gap, we analyzed qualitative data from Multi-site Family Study participants, 167 of whom were interviewed near the time of the male partner’s reentry. Using a modified grounded theory analytic approach (Birks & Mills, 2015), we tagged deidentified, verbatim transcripts with inductive and deductive codes in ATLAS.ti; reviewed data obtained from Boolean-type queries and identified themes; and prepared analytic memos on each theme.

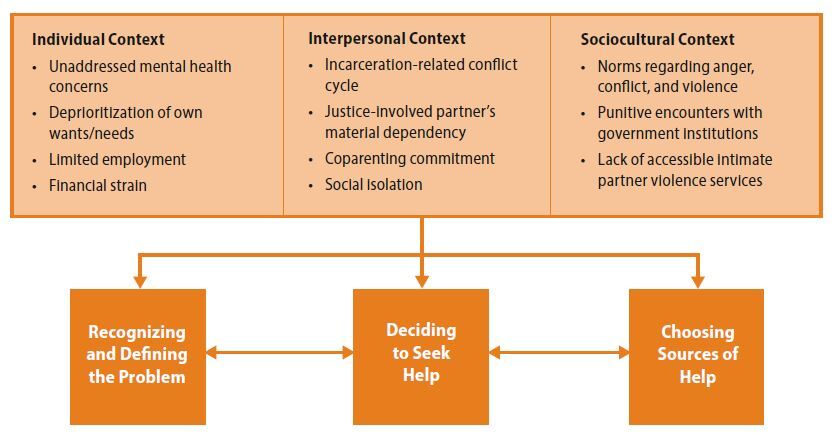

Liang et al.'s (2005) help-seeking model suggests three distinct processes involved in help-seeking among partner violence victims: recognizing and defining the problem, deciding to seek help, and choosing a source of support (Liang et al., 2005). All three are influenced by the individual, interpersonal, and sociocultural context (Figure 1) (Liang et al., 2005). Qualitative data from Multi-site Family Study participants indicates that, for couples affected by incarceration, distinct barriers can interfere with each of these processes.

Individual-Level Barriers to Help-Seeking

Victims in couples affected by incarceration described unmet behavioral health needs, particularly depression and post-traumatic stress, related to the incarcerated partner’s arrest, adjudication and imprisonment—which many found traumatic, grief-inducing, and depressing. Reasons for treatment needs going unmet included acute competing needs and time demands (Comfort et al., 2017) and a lack of accessible, individual mental health services in victims’ neighborhoods (Roll et al., 2013). Struggles with employment and finances (a key risk factor for partner violence victimization, Vest et al., 2002; Yakubovich et al., 2018) were prominent; couples faced daunting financial demands related to criminal justice involvement and related employment barriers (Schwartz-Soicher et al., 2011; Uggen et al., 2014; Visher et al., 2011). These contributed to a sense of limited options and difficulty prioritizing tasks (such as reflecting on an intimate relationship or evaluating potential sources of support) that were not critical to immediate survival.

Interpersonal Barriers to Help-Seeking

Interpersonal dynamics accompanying a family member’s incarceration and release can uniquely impede victims of partner violence from seeking help. Multi-site Family Study couples experienced phases of hopeful anticipation pre-release and “honeymoon” during reunification immediately post-release, followed by growing tension and the eruption of violence as the strains of reentry intensified. This made it difficult for victims to assess the health of their relationships at any given point in time, as behavioral patterns were constantly shifting with cycles of incarceration and reentry. Furthermore, reentering individuals were acutely dependent on their partners for basic needs like food and housing. This high-stakes dependency, along with couples’ co-parenting commitments, made it difficult for either partner to freely consider their relationship choices and diminished the relative importance of considering whether the relationship was unhealthy. Study participants also described deep social isolation, with only a small number of close and trusting relationships. Many adopted an interpersonal attitude of staunch independence and self-reliance that made them unlikely to consider seeking outside help and narrowed the field of potential sources of support.

Sociocultural Barriers to Help-Seeking

The sociocultural atmosphere of chronic deprivation and injustice that Multi-site Family Study couples recounted both provoked and normalized a sense of constant anger and unresolved conflict. In this context, it was often difficult to define episodic violence and controlling behavior in a relationship as distinct “problems.” Some victims reported being angry “all the time,” but their narratives suggested that it was difficult to differentiate their own anger at abusive treatment by their partners from the generalized anger they experienced at the circumstances of the male partner’s incarceration, the burdens it had placed on the household, and broader conditions in their communities. Among those who did identify their victimization as a problem, many suggested that violence (including partner violence and other forms of street and family violence) was commonplace in their communities; other research suggests that victims are less likely to decide to seek help in such contexts (Hayes & Franklin, 2017).

Finally, Multi-site Family Study participants recounted repeated punitive (or sometimes simply unhelpful) encounters with government institutions that shaped their attitudes toward formal help-seeking. Although many such encounters involved criminal justice institutions, they produced a generalized distrust, making it difficult for victims to consider seeking outside assistance or discern which sources of support might be most helpful. Victims expressed concern that their partners’ parole would be revoked if they disclosed their experiences to anyone—a consequence that was often difficult to countenance given their co-parenting commitments and desperate material circumstances.

The shortage of partner violence services in the low-income communities in which many victims lived (Iyengar & Sabik, 2009), the persistent lack of culturally specific intimate partner violence services for victims of color and those connected (directly or indirectly) to the criminal justice system (Oliver et al., 2006), and the flawed treatment accorded to intimate partner violence victims of color in legal protection processes (Williams & Jenkins, 2015) suggest that the difficulty study participants had in imagining meaningful, nonpunitive institutional help for their experiences reflected more than just a limitation in perspective.

Promoting Access to Support for Couples Affected by Incarceration

Couples affected by incarceration describe a set of formidable barriers to help-seeking for partner violence. Their stories call attention to the unique obstacles that many victims face in defining their victimization experiences as a problem, deciding to seek help, and identifying sources of help. They also suggest how first- or secondhand experiences with imprisonment and reentry from prison might exacerbate the already-significant obstacles to help-seeking that other marginalized victims commonly face: a general shortage of intimate partner violence services in low-income neighborhoods; a lack of culturally specific services; fearfulness and distrust of institutions; social isolation; cycles of “honeymoon” and revictimization; and the strains of parenting, poverty, and unaddressed behavioral health concerns that can overwhelm victims’ abilities to prioritize their own abuse-related needs and discernment processes (Burman & Chantler, 2005; Hampton et al., 2003).

The variety of barriers highlights an ongoing need for partner violence services and policies that respond to intersecting influences at each level of the Social-Ecological Framework (Carson & Anderson, 2016). Table 1 displays strategies to dismantle the multilevel barriers to help-seeking that Multi-site Family Study participants identified.

Some individual- and interpersonal-level barriers could be addressed (at least in part) by expanding the availability of formal supports tailored to the needs articulated by justice-involved individuals and their partners. Ongoing work by advocates and service providers to “reduce the gap between intimate partner violence (IPV) survivors’ expressed needs and the services that IPV programs most typically offer” may also be highly relevant to victims in couples affected by incarceration (Kulkarni, 2019). This work focuses on individualized service delivery in staff-client relationships that emphasize authenticity and shared power (Kulkarni, 2019).

Creating the kinds of environments in which intimate partner violence victims in couples affected by incarceration will seek and find meaningful help will require more than adjustments in service delivery approach, however. Indeed, researchers and domestic violence advocates have characterized “community change and systems change” (Kulkarni, 2019; Sullivan, 2018) or “robust systems advocacy” (Kulkarni, 2019) as an indispensable component of programs’ efforts to end violence. Meaningfully addressing the sociocultural barriers to help-seeking identified by Multi-site Family Study participants will require just such efforts. For example, longer-range strategies could replace punitive institutional practices in communities that have been heavily affected by mass incarceration with richer and more-effective preventive and protective functions that communicate the value of the individuals and communities served.

Conclusion

Efforts to support help-seeking by partner violence victims in couples affected by incarceration represent a key part of larger efforts in the fields of domestic violence and victim services to improve the accessibility of services in marginalized communities and better meet complex victim needs. Our findings suggest that involvement with the criminal justice system (whether directly or through a family member) introduces unique individual, interpersonal, and sociocultural barriers to defining one’s experiences as a problem, deciding to seek help, and selecting sources of help. Opportunities exist not only to tailor service delivery approaches in ways that overcome the individual and interpersonal obstacles that affect victims, but also to pursue longer-range shifts in public policy and community infrastructure that will address broader and more-entrenched barriers to help-seeking.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to participants in the Multi-site Family Study on Incarceration, Parenting and Partnering for sharing the experiences and insights that made our work possible. We also wish to thank the National Institutes of Justice, and particularly Senior Science Advisor Angela Moore, for supporting this research. Finally, we appreciate the anonymous peer reviewers whose feedback strengthened this work and the RTI staff who brought it to publication, including Pamela Williams, Claire Korzen, and Sonja Douglas.

The Post-Incarceration Partner Violence Study is conducted by RTI International with funding from the National Institute of Justice in the US Department of Justice, Grant Number 2016-VF-GX-0010.