Introduction

Many cancers are potentially avoidable through positive behavioral changes related to tobacco use, body weight, physical inactivity, alcohol consumption, diet, sun exposure, the use of tanning devices, and the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination to protect against cancers caused by infectious agents (Islami et al., 2024). Organizations participating in community-based health initiatives play a critical role in delivering evidence-based interventions (EBIs) that support cancer prevention behaviors such as healthy eating and active living. Examples of the types of organizations involved in these efforts include local governments (such as health departments and parks and recreation departments), school districts, and local nonprofit organizations. These initiatives support organizations in implementing programs and environmental and policy changes to improve population health, such as connecting sidewalk networks to provide safe routes for pedestrians, offering fresh fruits and vegetables at food pantries, and supporting parks and recreation master plans to ensure equitable space for physical activity. Best practices for evaluating community-based health initiatives include employing a theory-based evaluation approach (Judge & Bauld, 2001) and co-creation with the community (Judd et al., 2001). However, it can be challenging to evaluate community-based health initiatives because of their complexity, including multisector coalitions, multifaceted interventions, changing community conditions, and budgets and other resource constraints (Fry et al., 2018).

In this report, we describe the collaborative approach taken by RTI International, an independent scientific research organization, and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Be Well Communities™ project team (the latter hereafter referred to as the Be Well Communities team) to develop and implement the evaluation of Be Well Communities, a community-based, population health initiative for cancer prevention. It is important to note that RTI developed the evaluation with input from the Be Well Communities team and then conducted an independent evaluation of the initiative.

Given the comprehensiveness of Be Well Communities, the evaluation is a uniquely instructive example of a real-world evaluation approach with constraints often faced by evaluators, funders, and community organizations implementing interventions and collecting and reporting data. Consequently, we also share lessons learned from the evaluation process that may be useful for evaluators and program planners evaluating multifaceted community health initiatives like this one.

Finally, it should be noted that this report does not recount the findings of the process and outcome evaluation, which have been reported elsewhere (Loomba et al., 2024; Love et al., 2024; Oestman et al., 2024; Rechis et al., 2021, 2024).

Background on Be Well Communities

MD Anderson established Be Well Communities in 2016 (Rechis et al., 2021) to work with communities to address modifiable cancer risk factors by leveraging best practices in population health (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). Be Well Communities focuses on five key health areas for cancer prevention: healthy eating; active living; sun safety; tobacco-free living; and preventive care, such as cancer screening and HPV vaccinations. One framework used by this initiative is collective impact (Kania & Kramer, 2011) that centers on creating long-term change with organizations coordinating efforts around a common goal. Collective impact initiatives are defined by having a common agenda “supported by a shared measurement system, mutually reinforcing activities, and ongoing communication, and are staffed by an independent backbone organization” (Kania & Kramer, 2011).

Be Well Communities relies on the collaboration of a backbone organization, a Steering Committee for each community, and collaborating organizations. The Be Well Communities team serves as the backbone organization and is responsible for overall coordination and management, convening and fostering collaboration among multiple sectors, stewarding funds, aligning organizations to a common vision, building community capacity to shape health outcomes, and supporting evaluation of the initiative. The Steering Committee is a community-driven coalition composed of residents and local organizations that connect the initiative to the community, develop a Community Action Plan (CAP), monitor and support program implementation, and champion the initiative. Collaborating organizations are funded Steering Committee organizations—such as health departments, parks and recreation departments, schools, and local nonprofit organizations that implement EBIs tailored to the community. Collaborating organizations select and implement EBIs from established resources, including the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s What Works for Health (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2019) and The Community Preventive Services Task Force’s The Community Guide (Community Preventive Services Task Force, 2021). These resources provide information about EBIs that are scientifically supported to positively impact community health.

Be Well Communities has been implemented in three communities in the greater Houston (Harris County), Texas, area that have majority-minority populations (United States Census Bureau, 2023): Pasadena, Baytown, and Acres Homes. These communities were selected because data indicated they had elevated modifiable risk factors for cancer (such as high rates of obesity and tobacco use) compared with Texas and the United States overall (Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention, n.d.-a, n.d.-b) and the capacity to address needs associated with these risks (e.g., sufficient community infrastructure).

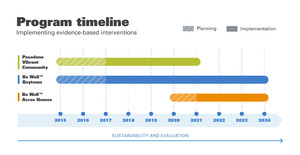

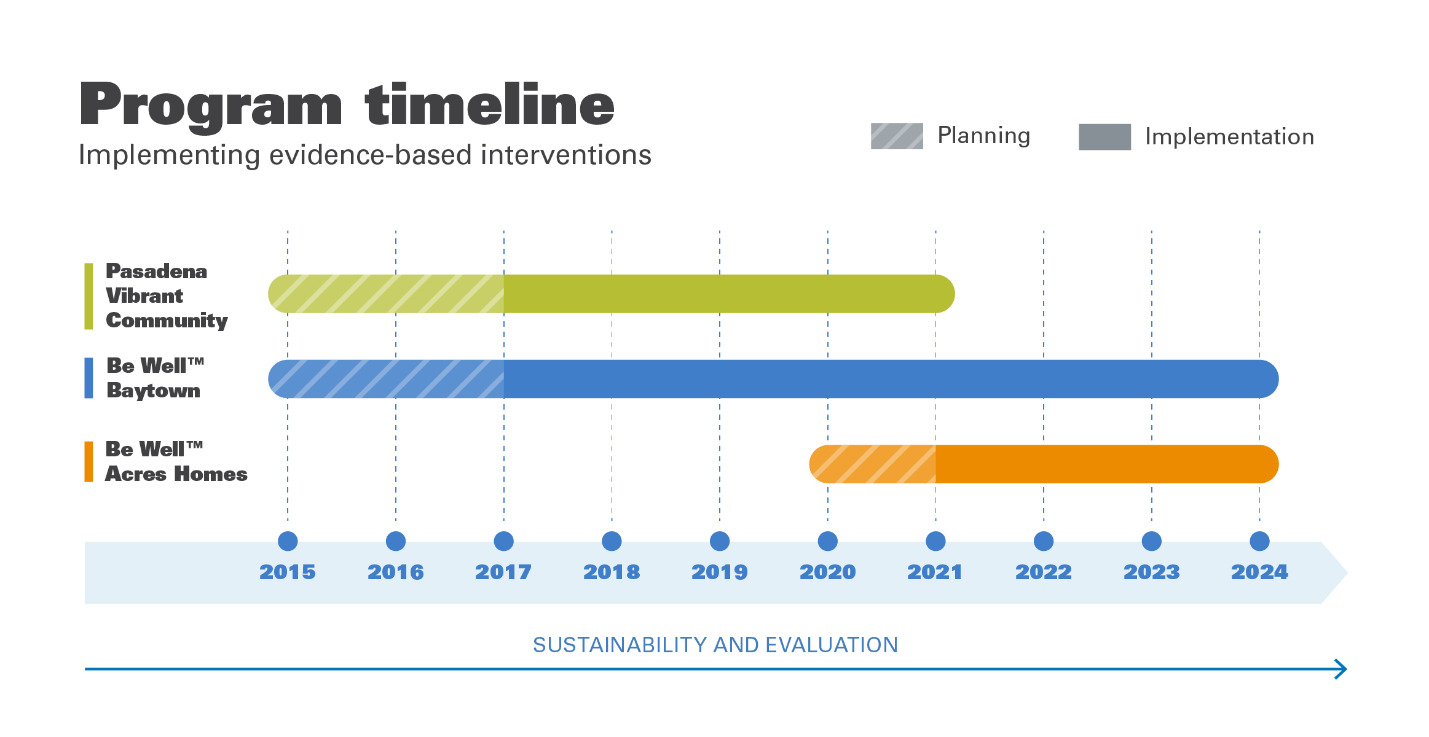

Figure 1 shows the staggered timeline for planning and implementation in these communities from 2015 to 2024. Communities implemented varying EBIs addressing different health areas according to community priorities (Loomba et al., 2024; Love et al., 2024; Oestman et al., 2024; Rechis et al., 2021, 2024). The key health areas focused on and the number of EBIs implemented varied each year as the initiative was expanded into additional health areas, additional collaborating organizations in a community offered programming, or communities started to sustain programs they were implementing. At the time of this paper’s writing, Be Well Baytown and Be Well Acres Homes are actively implementing EBIs, and Pasadena Vibrant Community is sustaining its efforts.

Evaluation Background and Planning

MD Anderson contracted with RTI to plan and conduct an external evaluation of Be Well Communities. The RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework guided the evaluation (Glasgow et al., 1999). RE-AIM is a well-established implementation science framework for planning and systematically evaluating community-based programs (Kwan et al., 2019) that contains the following dimensions: Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (Glasgow et al., 1999). Table 1 presents the evaluation questions aligned with the RE-AIM evaluation dimensions and the data sources used to address the evaluation questions.

Methods

Evaluation Plan

Evaluation planning involved RTI and the Be Well Communities team collaboratively delineating the evaluation questions and identifying the measures and data needed to answer each of the process and outcome evaluation questions (Table 1). The evaluation used a mixed methods approach, including qualitative data to understand the “why” and “how” that are reported in the quantitative data.

For each community, RTI and the Be Well Communities team collaborated to iteratively develop the evaluation plan. Because each community involved different types of organizations and combinations of key health areas and EBIs, a tailored evaluation plan was developed for each community. For example, Pasadena Vibrant Community only focused on healthy eating and active living, whereas Be Well Baytown implemented EBIs in those two key health areas plus sun safety, tobacco-free living, and preventive care (HPV vaccination and cancer screening). However, the evaluation plan for each community was based on a shared overarching logic model, evaluation questions, guiding principles, and the RE-AIM evaluation framework. The evaluation plans were developed at the initiative’s outset in each community and updated as needed to respond to any changes in the needs of the communities and programs implemented in them.

The same evaluation questions were included in the evaluation plans of the different communities (Table 1) and were revised across the communities over time. The evaluation questions were based on the RE-AIM framework (Glasgow et al., 1999; Shelton et al., 2020). Evaluation questions designed to measure initiative activity outputs asked about the extent to which EBIs were implemented, the extent to which community members were reached, and whether the five conditions of collective impact were achieved: common progress measures, common agenda, backbone organization, mutually reinforcing activities, and communication (Kania & Kramer, 2011). Evaluation questions designed to measure short- and intermediate-term outcomes asked whether the initiative achieved systems changes, what were the health-related outcomes, and whether the initiative had an impact on health-related outcomes. Systems changes include changes made to professional practices (i.e., changes in organizational workflows or processes that impact program delivery), to the environment (i.e., changes to the built environment), to policy (i.e., changes to explicit policies internal or external to organizations), and to funding (i.e., acquiring new grants or other sources of funding that promote program sustainability).

Logic Model

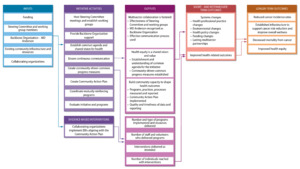

The evaluation plan included development of a logic model that was informed by the evaluation questions. Figure 2 shows the overarching logic model for all Be Well Communities including inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes that are shared between the communities. This figure illustrates how Be Well Communities aims to achieve its short- and intermediate-term goals of addressing modifiable risk factors for cancer and its longer-term goal of reducing cancer incidence and mortality. Additional community-specific logic models were also created to delineate the specific EBIs implemented by collaborating organizations and their anticipated short- and intermediate-term health-related outcomes (not pictured).

Evidence-Based Intervention Measures

The Be Well Communities team worked with each collaborating organization to develop SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable/Achievable, Relevant, Time bound) objectives (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 2024) and their associated evaluation metrics to guide implementation of specific EBIs. The evaluation used existing measures collected by collaborating organizations when available, such as measures already tracked for school interventions, and developed a limited number of new measures when needed. For example, the Be Well Communities team worked with one organization to add questions from an elementary school survey (Texas School Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey; https://sph.uth.edu/research/centers/dell/project.htm?project=3037edaa-201e-492a-b42f-f0208ccf8b29) to an existing evaluation tool at childcare centers (https://www.gonapsacc.org/) about the amount of time children spend being physically active outdoors to have a common measure for early childcare and elementary school children. The Be Well Communities team worked with other organizations to develop and implement surveys, such as a parent perceptions survey on safe routes to school interventions (https://saferoutesdata.org/downloads/Parent_Survey_English.pdf).

When possible, organizations implementing EBIs to affect similar outcomes used the same measures, and they worked together to identify and develop these measures. For instance, organizations implementing EBIs to increase healthy food consumption all tracked pounds of food distributed via internal tracking logs, whereas organizations implementing EBIs to increase sun safety all assessed, via a post-training survey, participants’ self-reported confidence in their ability to implement sun protective behaviors as part of their daily routine.

Collaborating organizations collected and aggregated data from program participants in accordance with the EBI measures noted previously—and submitted them to the Be Well Communities team using a standardized quarterly report template. The quarterly reports documented the organizations’ progress on objectives in the CAP, specifying EBIs for each collaborating organization and associated objectives and evaluation metrics, as well as barriers to meeting those objectives. The fourth-quarter report in each year included additional narrative questions to reflect on the entire prior year of implementation; for example, to describe opportunities and/or challenges encountered during implementation and if any support could be provided.

The Be Well Communities team provided technical assistance to organizations quarterly to refine their data reports and ensure data quality and consistency. RTI collaborated on these efforts to improve the consistency and quality of the measures over time. For example, RTI and the Be Well Communities team standardized language across measures—such as the use of the terms individuals, clients, participants, and patrons—to aggregate the reach of multiple programs more accurately. RTI also requested frequencies in addition to percentages to ensure that metrics were being calculated consistently and correctly across organizations and over time.

In addition to providing summary data in the quarterly reports, many of the collaborating organizations reported more extensive data on health-related outcomes in supplemental data reports. For example, a community college conducted an annual survey of students, faculty, and staff and reported data on knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to tobacco use, with a full report outlining all quantitative and qualitative results. Also, to evaluate the impact of Coordinated Approach to Child Health (CATCH, n.d.) school health program activities, school districts collected and reported System for Observing Fitness Instructional Time (SOFIT) (Mckenzie, 2015) data describing children’s engagement in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and the results from the School Physical Activity and Nutrition (SPAN) survey that measures students’ physical activity and nutrition attitudes and behaviors (Hoelscher et al., 2003).

RTI developed stakeholder surveys and interviews to answer evaluation questions that could not be addressed through data collected by collaborating organizations in their quarterly and supplemental reports. The surveys and interviews are described in more detail in the sections that follow.

Evaluation Activities and Implementation

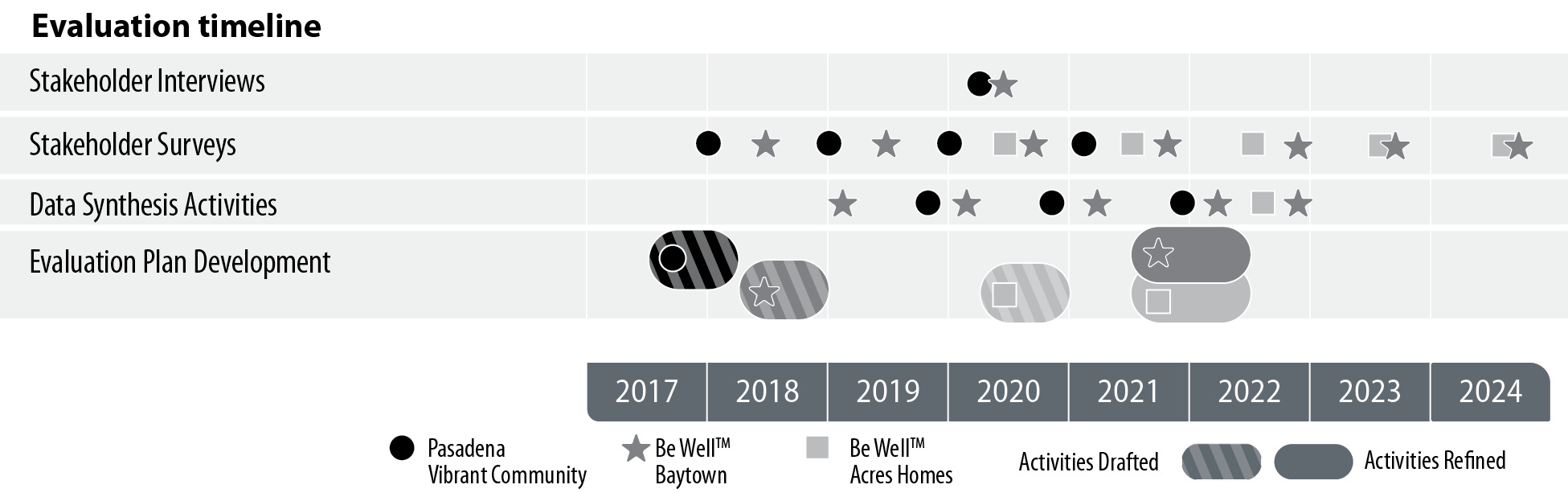

As part of evaluation activities, RTI administered annual stakeholder surveys, conducted interviews with key stakeholders, and synthesized quarterly and supplemental data reports submitted by collaborating organizations. Figure 3 shows the timing of the evaluation activities by year (x-axis) and by evaluation activity (y-axis).

Annual Stakeholder Surveys

Each year, active members of the Steering Committee were invited to complete a survey that assessed implementation of initiative activities; partnerships; the initiative’s goals, focus, and progress; Steering Committee roles; participation in the initiative; expected outcomes; sustainability; and the five domains of collective impact. The survey aimed to measure the nature and scope of multisector collaboration within the community and to document the community’s shared value of and vision for health, as measured over time. Survey items were similar across years and communities to allow for comparisons. Items were tailored to reflect the goals of each community and the EBIs being implemented, the EBIs removed, or the EBIs added to reflect changes in the initiative’s progress or modifications to the evaluation questions of interest. RTI administered the surveys through an online survey platform.

Stakeholder Interviews

RTI conducted semistructured telephone interviews with a subset of representatives from collaborating organizations with high levels of involvement in the initiative, such as being a funded collaborating organization or attending a majority of the Steering Committee meetings. The interview questions expanded on the quantitative findings by inquiring about barriers and facilitators to EBI implementation, health outcomes among EBI participants and the community more broadly, systems changes, partnership development, initiative expansion and sustainability, and lessons learned.

Synthesis of Quarterly and Supplemental Data Reports

RTI synthesized the data from all data sources into annual evaluation reports for each community, which were prepared for the Be Well Communities team. These evaluation reports addressed the evaluation questions, areas of excellence, areas for improvement, and limitations. The reports also included an assessment of the progress of the initiative and its overall impact, including estimates of the total number of youth and adults reached through EBIs, barriers to EBI implementation, health-related outcomes, systems changes, and sustainability.

Results

Through the evaluation planning and activities, RTI and the Be Well Communities team developed a robust evaluation plan and processes that allowed data to be collected that answered the evaluation questions. In turn, this has helped guide ongoing program implementation and long-term sustainability. The following sections present several key lessons learned from the evaluation process and provide suggestions for program implementers and evaluators based on these learnings.

Using an Evaluation Framework

Given that evaluation frameworks are underused and/or underreported in the literature (Fynn et al., 2020), one strength of the Be Well Communities evaluation is the use of RE-AIM as a framework for the evaluation (Glasgow et al., 1999). RE-AIM is one of the most frequently applied frameworks to evaluate public health interventions because it improves understanding of the effectiveness of interventions implemented in real-world community settings and is useful for evaluating interventions at the individual level and other socioecologic levels (e.g., community, system, policy) (Glasgow et al., 1999; Shelton et al., 2020). The evaluation helped the Be Well Communities team understand objectively if they were fostering multisector collaboration and making health equity a shared vision and value.

Incorporating Efficiencies

Evaluations of interventions targeting multiple organizations, communities, and behaviors can be costly (Arteaga et al., 2015; MacDonald et al., 2006; Rohan et al., 2019). The Be Well Communities evaluation approach created efficiencies in several ways. First, it used the same evaluation framework and overall approach for multiple communities, including collecting consistent data across communities. Second, leveraging the same evaluation framework each time meant that lessons learned could be easily incorporated into the next community evaluation plan, leading to a more expeditious, and presumably less costly, approach. Third, because the evaluation was conducted for multiple communities implementing similar EBIs, it garnered the benefit of efficient scale-up as the Be Well Communities team was able to incorporate lessons learned from one community into the next.

Leveraging Known Effective Strategies

By deploying EBIs from existing tools such as the What Works from Health (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2019) and The Community Guide (Community Preventive Services Task Force, 2021), the evaluation plan included metrics and measures that had already been identified as known outcomes for each intervention. For example, for communities implementing school gardens, outcomes such as increased willingness to try fruits and vegetables and increased fruit and vegetable consumption were factored into data collection as a starting point. This allowed for comparison of the results between communities and with other approaches. It also provided a sense of the expected outcomes and significantly informed direction for those establishing the initial evaluation plan and related metrics.

Developing a Flexible Evaluation Plan

Given this complex, multiyear evaluation and the need to maintain alignment with the evaluation framework, it was necessary to revisit and update the evaluation plan to reflect the needs of the communities over time. For example, the evaluation questions were revisited to reevaluate health equity (assessing reach to populations experiencing health-related disparities) and the cost of intervention activities (e.g., cost and cost-effectiveness of sun safety interventions) that are integral to sustainability (Shelton et al., 2020), which were then appropriately integrated.

The Be Well Communities team continued to invest in the evaluation and expand it, and incorporated feedback learned through the evaluation into initiative implementation, such as altering communication strategies to address reported needs of the Steering Committee by providing more clarity of the initiative’s goals, common measures, and aligned activities. Further, the Be Well Communities team was flexible with collaborating organization staff turnover and trained new staff members and adjusted evaluation metrics as needed while continuing to maintain the data collection guidelines.

Leveraging Existing Data

One strength of the Be Well Communities evaluation plan is its reliance on data that are already collected by collaborating organizations as a part of intervention implementation, thereby reducing burden on these organizations to gather additional data, and potentially supporting adherence to evaluation activities.

The Be Well Communities team’s provision of technical assistance to collaborating organizations was also critical in helping them collect and report accurate and timely data. Over the course of the initiative, the Be Well Communities team helped to build evaluation capacity within the collaborating organizations. Collaborating with organizations and gaining their buy-in while defining outcome measures and establishing implementation metrics as part of the CAP made it more feasible for organizations to collect and report data. Real-world, community-based evaluations need to prioritize outcomes and focus limited measurement and data collection resources accordingly, in terms of both evaluation funding and resources of community-based collaborating organizations, including time and skills/training in data collection and reporting/evaluation.

Further, collaborating organizations were highly engaged in the measures and evaluation development. For example, engaging the collaborating organizations in setting metrics ensured that it was feasible to collect the data for the evaluation. Over time, the organizations have increased their understanding about the importance of collecting and reporting data for purposes of evaluation and have become increasingly skilled at setting metrics and milestones, which has continued to enhance the overall evaluation.

Discussion

This case study illustrates an approach for evaluating complex, population health, community-based initiatives and the lessons learned while accounting for real-world funding, time, data, and other contextual constraints. The Be Well Communities evaluation examines a multifaceted, comprehensive, community-driven cancer prevention initiative conducted across three communities, which contrasts with initiatives that often address interventions for one specific cancer prevention or health behavior (Copeland et al., 2019; McDonough et al., 2016), focus on a single community (Hempstead et al., 2018), and/or intervene at one level of the socioecological model (King et al., 2019).

Additionally, the Be Well Communities evaluation approach demonstrates that aligning data sources across organizations implementing EBIs focusing on the same outcomes and using multiple methods of evaluation can facilitate a more accurate description of an initiative over time and enable gaining a fuller picture of the initiative’s impact. Implementing the evaluation plan and its associated activities demonstrated the importance of collaborating with the Be Well Communities team, as the backbone organization, to gain the collaborating organizations’ buy-in and participation in evaluation activities. The provision of technical assistance by the Be Well Communities team also helped build the capacity of the collaborating organizations to engage in evaluation activities, including the development and use of shared measures and quarterly reporting to ensure complete, accurate, and timely data.

Consequently, the Be Well Communities evaluation approach and its demonstrated successes and lessons learned can serve as a dynamic model for other communities in the United States seeking to evaluate complex, community-based interventions to improve population health and more specifically to reduce modifiable cancer risk and make progress toward greater health equity.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the organizations that serve on the Steering Committee for Be Well Acres Homes, Be Well Baytown, and Pasadena Vibrant Community, alongside residents of those communities. We also wish to acknowledge Jeffrey Novey at RTI International for contributing his editorial expertise. This work was supported through the generous philanthropic investments in Be Well Communities, MD Anderson’s place-based approach for cancer prevention and control. RTI International staff time for developing the manuscript was funded by the organization’s internal resources.