Introduction

Today, primary education remains pivotal in the academic and personal development of students.[1] According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) (2013), education programs primarily aim to teach students basic skills in reading, writing, and mathematics, and to lay a solid foundation for learning and understanding essential areas of knowledge and for personal and social development.

As society evolves, however, the challenges that primary school teachers face in their teaching practices become more evident. Rubio Hernández and Olivo-Franco (2020) referred to this reality and emphasized that “new demands and expectations have emerged in the school environment, derived from the social, economic, and cultural changes that have occurred in many different areas (Day, 2005)” (p. 8). Significant events expose this relationship between the phenomena in the social context and their direct impact on education—including, for instance, the COVID-19 pandemic, which impacted and posed significant challenges for education systems (Mann, 2020; UNESCO, 2020).

In this regard, international organizations such as the World Bank, UNESCO, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), Human Rights Watch, and the Organization of Ibero-American States (OEI in Spanish) concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic represented the greatest loss and setback in learning that education has ever experienced, exacerbating achievement gaps in education for each year of disruption, worldwide (Palacios Mosquera & Palacios Scarpeta, 2023). This finding is demonstrated by the results of the latest report of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which found that in the case of the Latin America and Caribbean region, “three out of four students perform poorly in mathematics, and half lack basic reading skills” (Arias Ortiz et al., 2023). The results of international assessments in Guatemala in 2019 showed that 39.3 percent of grade 3 students reached the minimum reading proficiency level, and 34 percent in mathematics. In grade 6, 15.1 percent of students scored above the minimum expected proficiency level in reading, and 6 percent in mathematics (UNESCO, 2022). Although there is not yet post-pandemic information on educational performance in primary school in Guatemala, the World Bank (2021) noted that learning poverty—defined as the percentage of 10-year-old children who cannot read or comprehend a simple text—may have grown from 51 percent to 62.5 percent in Latin American and Caribbean countries.

Undeniably, recovering lost learning requires programs, collaborations, and institutional actions that support teachers at all levels, enabling their continuous development and updating of skills, including those essential for effective teaching (Sanchez Mediola et al., 2023). In addition, the training of such teachers—both at entry level and in their continuing professional development—needs to focus on competencies and practical application of knowledge (Pérez Gómez, 2013). In the post-pandemic context, with the widened gaps in opportunity and learning caused by long-term school closures, teachers’ ability to collect and analyze information about their students’ skills to provide supportive, tailored lessons becomes even more important.

In this regard, one tool to address these challenges is action research—defined as an approach that systematically studies problematic situations in order to take action to change them, by dynamically combining research and action. In the education context, action research is a process of reflection through which teachers do research and improve their own educational practice (Pine, 2008).

As a training strategy, action research can be perceived as a way of operating based on what works in the classroom (Bergmark, 2022). Furthermore, teachers have the opportunity to ask questions about the everyday problems they face, and can devise solutions, thus engaging in systematic inquiry to bring about changes in practice and obtain better results for the problems they identify (Bergmark, 2022; Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009; Messikh, 2020; Mills, 2017).

For authors Fullan (2010), Hawley and Valli (1999), and Putnam and Borko (2000), as cited by Manfra (2019), these action research learning experiences must be connected to daily, sustained, long-term practice if they are to effect change in teaching. O’Connor et al. (2006) added that action research is a tool that helps teachers discover strategies to improve teaching practices. Action research and teachers’ valuing of their knowledge for their own development are also important components of the Funds of Knowledge notion, which assigns value to people’s skills, knowledge, and experiences in order to connect them to learning (Ambrosy Velarde et al., 2024).

Action research plays a pivotal role in improving teachers’ practices by encouraging them to actively examine their own teaching methods and the needs of their students in order to make informed decisions (Crawford, 2022). According to Mertler (2021), unlike trial-and-error approaches, action research follows a more structured and systematic process, allowing teachers to purposefully change their teaching strategies based on evidence and reflection. One of the recommendations that UNESCO (2021) made to teachers was to actively engage in educational research, based on reflection on their practices in order to produce knowledge.

Regarding research competencies, Rincón Gonzáles and Mujica Chirinos (2022) referred to teachers’ “mastery of skills, knowledge, and values as related to knowing how to do research, knowing how to be a researcher, and knowing how to transfer the knowledge obtained from research” (p. 30).

Muñoz Giraldo et al. (2001) provided another interpretation, noting that research competencies “are those necessary for educators to be able to interpret, argue, suggest alternatives, ask questions, and write based on the pedagogical experience in accordance with the typical problems of the classroom and the school” (p. 145). Individuals to be trained as research teachers require essential general and individual characteristics and skills, including the ability to ask questions, observe, experiment, register, analyze, interpret, write, summarize, be critical and self-critical, foster cooperation, and maintain values (Moscoso-Ramírez & Carpio Cordero, 2022). When teachers develop research skills, they can search, select, reconstruct, and use knowledge critically and actively, adapting to specific circumstances that arise (Zetina Pérez et al., 2017, p. 5).

In some Latin American countries, including Guatemala, educators’ main task is to teach; research is not typically part of what teachers are expected to do. Paredes-Chi and Castillo-Burguete (2021) noted that research as a practice within teacher preparation programs is not well established, while Palencia Salas (2020) added that these research skills are more likely to be put into practice in a university environment. Some authors have found that experiences in action research with teachers generated lessons in teaching, research, and collaboration. As regards action research, teachers have gained knowledge about research results; come to understand and use research methods to document and analyze teaching practice (Bergmark, 2022); and learned about ways of teaching, research skills, critical awareness, motivation, and consideration for their students (Edwards, 2016).

Based on the above, we emphasize the key role of research experiences in strengthening research skills. Teachers can turn these skills into an essential catalyst for pedagogical improvement. The objective is to bridge gaps in learning based on classroom research processes that the teachers can implement or reflect upon.

This study explored the reflections of teachers participating in a training program that focused on action research. The purpose of this program was to support first-, second-, and third-grade primary school teachers in carrying out a research process in their classrooms, addressing specific problems identified in reading/writing, and mathematics. Analyzing the participants’ reflections yielded significant lessons that shed light on the effectiveness of this approach to teacher training.

Context

Guatemala is a lower-middle income country with high levels of inequality and a history marked by a rich Mayan culture, centuries of Spanish colonialism, and a 20th-century civil conflict that spanned more than three decades. Since the signing of the peace accords that put an end to the conflict in 1996, Guatemala’s public education system has experienced significant challenges and transformations. The accords aimed to address problems stemming from the decades of civil conflict, including social inequality and lack of access to basic services, such as education. In fact, one of the main objectives of the agreements was to improve access to and quality of education, particularly for rural and indigenous groups.

The quality of education has been a persistent challenge, and many public schools still lack adequate resources, trained teachers, and infrastructure. Successive governments have implemented curriculum reforms to promote bilingual education and culturally relevant content, but implementation has been uneven across the country. Teacher professional development has been prioritized, but many educators still work under challenging conditions, such as shortages of teaching and learning materials, lack of access to technology and supplies, problems in mobilizing enough teachers to schools, and other situations in the contexts in which they work. These challenges affect the consistency and quality of education provided to students, especially in the altiplano (highlands), a region with a majority indigenous population.

The policies of the national education system acknowledge this complexity and the continuous effort to improve the quality of education, starting with teaching as a key factor. The importance of building teachers’ capacities as the main effort of the educational system is revealed in the policies aimed at the training, evaluation, and management of human resources of the National Educational System (General Directorate of Educational Evaluation and Research [DIGEDUCA], 2021). The Teacher Researchers (Docentes Investigadores) program assists in this approach and provides a learning space for teachers to experience research in the classroom and be part of this continuous professional development. Ureta et al. (2019) posited that continuous professional development in Guatemala is related to processes of teacher support, onboarding, updating, professionalization, and/or coaching.

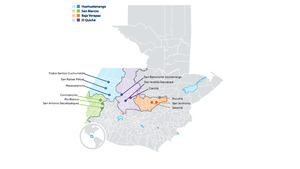

In this context, the “Basic Education Quality and Transitions” (BEQT) Activity, funded by USAID and implemented by RTI and its partners Funcafé, Funsepa, Wayfree, and UVG, is supporting the Ministry of Education (MINEDUC) in its efforts to improve access to high-quality basic education, especially for vulnerable and marginalized groups in the altiplano (see Figure 1). The main purposes of the Activity are to help improve the development of basic skills in reading, writing, and mathematics; to encourage social and emotional skills among children and youth, indigenous students, girls, and people with disabilities; and to increase completion and transition rates from primary to secondary school in Guatemala’s highlands. An important focus is on improving transition rates from primary (sixth grade) to the first year of secondary (seventh grade); in the municipalities supported by the Activity in 2023, only 59 percent of students who completed sixth grade subsequently enrolled in seventh grade. The Centro de Investigaciones Educativas (CIE) of Universidad del Valle de Guatemala—as an RTI partner—developed and implemented the Teacher Researchers program to support teachers in improving their classroom practices. The action research program engaged teachers in identifying and bridging gaps in mathematics, reading, and/or writing with students in grades 1–3.

These teachers were selected via a convenience sample through a direct call to the schools made by the local education ministry of the participating municipalities. During this cohort, 121 grades 1–3 teachers from public primary schools in Guatemala completed the program. They represented 12 municipalities in the departments of Baja Verapaz, Huehuetenango, Quiché, and San Marcos.

The program was structured in three phases: the planning phase, which included onboarding the trainees, determining the characteristics of the action research design, having the teachers identify gaps, and proposing the plan to be implemented; the implementation and monitoring phase; and the evaluation and lessons-learned phase.

The teachers who participated in the reflection workshops held in each municipality identified the challenges and benefits of conducting research in the classroom. Two experts hired by the Activity, one specializing in reading/writing and the other in mathematics, provided guidance through training workshops and support during the process.

The full training included one briefing session, two workshops, and four support sessions with the participants. The purposes were to:

-

analyze the results of a diagnostic evaluation,

-

identify the students’ skills and learning gaps,

-

support the identification and application of teaching strategies to bridge the gaps, and

-

guide the teachers in analyzing and documenting their experiences during the process, so that they could replicate it with other students.

In total, 9 hours were dedicated to face-to-face sessions, and 4 hours of remote support were offered to each teacher.

Throughout the program, information was collected on the process of reflection, planning, and implementation; on the implementation of the activities; and on the teachers’ achievements and lessons learned. This article focuses on the information collected in connection with the teachers’ research proposals to address the gaps and learning the teachers themselves had identified.

Through this research, we intend to show what the contributions and lessons learned from the action research were, and how the application of research skills fostered changes in the educational practices of the primary school teachers who participated in the program. This article aims to clarify the transformative potential of this experience, and also to offer valuable perspectives for the design of future teacher training programs in the field of classroom research.

Research Question

In this context, the question arises: What lessons can be learned from an action research experience to address educational gaps in the classroom?

Methods

This research was developed with a qualitative approach and a descriptive design. To select the participants, purposive sampling was used, which is defined by Campbell et al. (2020) as the type of sampling used to select elements with a high probability of providing useful information, to optimize research resources, and to determine essential members of the sample according to the objectives of the study.

Part of the process was to introduce the research methodology to be used. It was based on three main phases that are present in several established action research models and that are related to the development of certain research skills:

-

Planning: Observe, identify the problem, gather information, review literature, research and plan the strategy or action.

-

Implementation: Implement the plan, collect information or data, analyze it, identify improvements, adjust, evaluate.

-

Reflection: Prepare a summary of results, systematize (i.e., analyze and organize to reveal the logical steps in and elements of a process), share results, reflect on the whole process.

(Adapted from Clark et al., 2020; Greenwood & Levin, 2007; Phillips & Carr, 2013; Pine, 2008; Riel & Lepory, 2014)

As part of the program, participating teachers completed an instrument that aimed to consolidate the various aspects of the action research process implemented by each teacher, to make it feasible to report on the most important components of that process. The responses that teachers wrote on paper were transcribed into an Excel-based matrix; an example from a reading/writing teacher is provided in Table 1 and from a math teacher in Table 2. This was the information that our research team analyzed.

Participants

For this research, out of the 121 teachers, we separated out the 108 teachers who met the criterion of having provided some information to the questions in the survey, accounting for 89 percent of the original group. In total, 55 teachers worked in the area of reading/writing and 53 teachers worked in the area of mathematics. Thirteen teachers were not included because they did not provide information that could be analyzed. Some of them participated only in the in-person workshops and did not record any information on their research process. Others presented only photographic evidence of an activity they had carried out in class.

The Ministry of Education authorized the BEQT Activity to implement this program with teachers. The UVG Ethics Committee reviewed the application and signed off on the study. The present analysis uses deidentified data that were collected during the program.

Method of Analysis

We performed a content analysis of the experiences reported by the selected teachers, identifying categories significantly related to situations, contexts, and activities, and on various topics such as problems, strategies, and processes, among others (Vives Varela & Hamui Sutton, 2021).

For the coding process, one researcher coded the teachers’ information into categories and a second researcher confirmed the coding of the categories. Both used a manual coding process in Excel, assigning a different color to each category and marking the coded texts with that color. Lastly, both researchers came to an agreement on the proposed coded categories. The coding review process also involved checking that the subcategories were related to the three main areas of analysis on which this study focused; see Table 3.

Results

We analyzed the reflections reported by the teachers who completed the program, emphasizing the main lessons learned from the research process, the problems identified, and the results observed among the students.

Lessons Learned About the Research Process

Regarding the teachers’ skills and lessons associated with the action research process, they reported that they had applied research-related skills such as observing and evaluating problems in their context; searching for and analyzing information; and applying, evaluating, and reflecting on new teaching strategies. The teachers reported having geared this process toward exploring alternatives to help them address the problems they had identified in their classrooms. Although they recognized research as a tool to innovate and improve the quality of educational delivery, we observed in the systematization responses some challenges in posing questions, describing the problem, and connecting the parts of the action research methodology (approach, justifications, intervention). Table 4 highlights comments from teachers reflecting their experience with research.

These results matched the evidence found in other studies, which underscored an increase in recent years in the number of teachers who have conducted research involving reflecting on themselves and their own educational practices, and who have sought and implemented solutions to the difficulties they detected in the classroom (Palencia Salas, 2020). In this regard, research is increasingly necessary to identify and diagnose educational, social, institutional, and personal needs in the search for ways to promote significant changes in educational practices, in the teaching and learning process, and in the organization of educational institutions, among others (Muñoz Martínez & Garay Garay, 2015).

Lessons About Strategies Used

Teachers emphasized the importance of implementation and application, given that they were able to put the strategies they selected into practice in their classrooms to address the gaps they had identified. The teachers who participated in the program and reflected on their experience noted especially significant lessons related to applying new teaching strategies, and updating some strategies or reinforcing others, as a direct result of the research process they carried out. Teachers mentioned using innovative strategies that they had not used before this program, or activities that they had never previously implemented in their classes even if they were not necessarily innovative techniques. Table 5 highlights comments from teachers reflecting their experiences with applying the strategies raised by the research.

Table 5 is evidence of how research was an effective means for addressing teaching practice in the sense that, in addition to sparking a critical attitude among teachers toward specific educational issues, it aimed to help them more deeply understand and analyze certain problems in a given educational context, with the goal of finding alternatives for transformation and solutions (Morán Oviedo, 2004). Therefore, action research continues to be one of the modalities most used by teachers seeking to transform their own practices (Sanahuja et al., 2020).

This finding has been confirmed by prior studies focused on this subject, which have shown progress in applying research processes to improve teaching practices and educational innovation, and ultimately to help improve teaching competencies (Núñez-Rojas et al., 2021). Specifically, it has been found that research in education sharpens reflection processes, spotlights important issues, clarifies problems, and fosters debate and exchange, thus improving understanding, flexibility, and adaptation in the search for improving problem-solving skills (Catalán Cueto, 2020).

Other Lessons Learned by Teachers

Another noteworthy aspect of the lessons reported by the teachers who participated in the program is systematization, understood as the critical analysis of one or more experiences which—when organized and reconstructed—reveal the logical sequence of the process, the elements involved, the ways in which they relate to each other, and why they do so (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], 2004). The teachers referred to this process when they reflected on the importance of having guidelines, planning, and structure, as well as collecting information with a purpose. Similarly, recognizing evaluation and monitoring as fundamental for adequate follow-up of students became evident. And a commonly mentioned element was discovering the needs of their students, as well as knowing that they learn in different ways, in order to select the strategies to use. The terms that stood out within this coding category are presented in Table 6.

In this context, we confirmed that systematization is an effective educational process. This process allows for integrating ideas, concepts, knowledge, paradigms, and personal experiences with practice. The objective is to rethink and combine new knowledge with previous knowledge, shifting from isolated and private knowledge to organized and public or shared knowledge (Aranguren Peraza, 2007).

In addition, Table 7 shows other lessons learned secondary to the research process. These lessons relate to the importance of sharing experiences with other teachers. They also emphasize teamwork, effective communication, the use of technological resources, the search for innovation, persistence, and time organization.

Additional quotations in Table 8 show that the main lessons reported by teachers related to action research as a training strategy; the reinforcement of research skills; and the use of new, planned didactic strategies in the classroom.

Identified Gaps

Regarding the gaps identified, we found that teachers focused on the two areas of reading/writing and mathematics identified problems among their students in the development of competencies in the basic areas of each subject (see Tables 9 and 10). In addition, we found that reading/writing teachers identified other types of contextual problems that they believed were affecting this area. Their conclusions are consistent with the literature, which indicates that the mastery of mathematics, reading, and writing skills is fundamental, but that a considerable percentage of students finish compulsory schooling without reaching the expected proficiency levels (Orrantia, 2006). Additionally, in the specific case of reading/writing, although a series of complex mental processes is involved—such as perception, memory, cognition, metacognition, inferential capacity, and consciousness (Montealegre & Forero, 2006)—the process is also closely linked to the individuals’ social and contextual situation (Simbaña-Haro et al., 2023).

Results Observed in Students

After they had implemented new teaching strategies to address the identified issues, teachers reported changes in the development of reading/writing and math skills among most of the students (see Table 11). These changes were reflected in the students’ interest and motivation to learn, as well as teachers’ reports that they noticed most students making progress or improvements in the skills they were working on. Similarly, teachers identified students who were having difficulties developing these competencies and were able to follow up with them. These responses align with the ideas presented by Benítez Galindo (2016), who noted that:

With the intent and spirit to improve their practice, teachers will become rigorous researchers of themselves, and will take action in a planned manner, based on their own research; in addition, they will develop a project that involves strategies, activities, and actions that significantly transform their daily work, focusing on the students’ educational processes. (p. 45)

Through this action research experience, we assessed the metacognitive and reflective processes of the participating teachers in relation to their own educational practices. In this regard, Castellanos Galindo and Yaya Escobar (2013) argued that “explaining and problem-solving in teaching, in the form of a reflective exercise, is a tool to broaden the view of one’s own actions and to conceptualize what is being accomplished” (p. 5).

Along the same lines, Fourés (2011) underscored that “the use of metacognitive processes would help teachers create and establish these relationships by reviewing and recognizing their own knowledge and planning strategies used in their daily practice” (p. 156). In that sense, a noteworthy point is that this training program gave teachers the opportunity to evaluate and understand the impact of their teaching methods on student learning. It allowed them to identify effective strategies, as well as to question and analyze their own actions, as a means to identify areas for improvement.

Teachers recognized the importance of adjusting their practice to meet students’ changing needs, which is essential to improve educational quality, foster professional development, and ensure effective adaptation to the demands of their own educational contexts. In addition, teachers who participated in the training program highlighted three main aspects: the importance of continuing education and professional development for teachers, the importance of developing teaching competencies, and the importance of developing research competencies in the interest of addressing the identified needs of their students.

We recognize that this analysis is based on the teachers’ perceptions and how they viewed the results or changes regarding the use of strategies to address an identified learning gap. We did not have data that would allow us to verify the changes or results they mentioned. In other words, a study limitation is that the process of reflection and the use of strategies to address educational issues in the classroom occurred only while the teachers were participating in the program, and therefore we have no further information about their ongoing adoption of the changes within their regular teaching practice.

Discussion

Immersion in the action research process provided opportunities for teachers to become more aware of their students’ specific difficulties in the areas of reading, writing, and mathematics, and to develop skills to plan and implement teaching strategies tailored to their students’ specific needs. Similarly, they recognized the importance of monitoring and evaluation as core items for effectively following up the development of competencies in these curricular areas.

Notably, action research played a fundamental role as a catalyst for continuous improvement in the classroom. Teachers addressed the problems identified, and integrated planning, reflection, and action into their teaching practices. This change fostered a dynamic and adaptive learning environment, where teachers were constantly evaluating and adjusting their methods based on feedback and observed results. In addition, evidence emerged of increased confidence and self-efficacy among the participating teachers. This self-confidence was manifested in the implementation of strategies derived from the research and in the teachers’ willingness to share their experiences and learning with their peers, thus fostering a collaborative culture in their educational communities.

The results of this study suggest that the development of research skills, through a training program focused on action research, can become an effective catalyst for teachers to reflect on their work, thus influencing their ability to identify learning gaps and address them with selected strategies. This approach not only can be effective for addressing problems in reading/writing and mathematics, but also can promote a culture of continuous improvement, autonomy, and collaboration among teachers. Furthermore, these findings have important implications for the design of teacher training programs that seek to positively impact the quality of educational delivery, especially in complex contexts such as those in Guatemala.

Informed by this experience, we suggest two possible paths for expanding and institutionalizing action research practices for teachers in Guatemala. The first is through the system of in-service supervision and support—for example, by incorporating an additional module into regular teacher trainings. The second is institutionalization within universities as part of their initial teacher training courses. In both cases, the strengthening of action research practices could start simply, with tasks such as reviewing the results of formative tests and reflecting on what skills teachers could emphasize in their next lesson. As we observed with the present study, assessing reflective processes and encouraging curiosity are viable ways to help teachers feel empowered to improve their own educational practices.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the current study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Authors’ Contributions

Ana Aidé Cruz Grünebaum: Author. Leader of the study, research idea, contribution to the analysis plan, literature review, data analysis, data coding, article writing, corrections and revisions, edits. Adding missing information in all sections and addressing reviewer comments. Preparing research protocol, making corrections, giving instructions to the researcher writing the first draft of the article. Restructuring the first draft of the article.

Kevin Renato Rojas Sandoval: Author. Coding, data analysis, data interpretation, preparation of literature review of first draft, writing article first draft.

Sophia Verónica Maldonado Bode: Coauthor. Contributions to title, observations in literature review, analysis, and conclusions. Follow-up session to adjust observations with author. Review of final UVG versions before first submission to RTI.

Amber Gove: Coauthor. Revisions of article submitted to RTI. Revision of portions of the literature review, data analysis, presentation of results. Contributions to discussion section. Writing context section. Review of final versions. Time spent on follow-up sessions; submission to RTI Press.

Jennifer Elizabeth Johnson Oliva: Coauthor. Session to inform authors about the program and to clarify and resolve doubts about program implementation and information collected in the field. Contributions to the second version of the draft related to the introduction, context, program information, and information retrieval for analysis.

Acknowledgments

This co-publication was made possible by the generous support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this co-publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and RTI International and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

RTI Press Associate Editor: Lissette Saavedra

Published in cooperation with Editorial Universitaria Universidad del Valle de Guatemala. The Spanish-language version of this publication, Docentes investigadores en Guatemala: Aprendizajes de una experiencia de investigación acción para abordar brechas educativas en el aula is available from https://www.uvg.edu.gt/servicios/volumen-46/.